“The Old Witch has landed” was a much recurring phrase on Chinese social media on 2 August 2022. The so-called “Old Witch” was US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, and for the entire day, anyone who was online was closely following the latest developments regarding her potential visit to Taiwan.

Up to the moment the plane touched down, Chinese bloggers and political commentators came up with different prediction scenarios as to whether Pelosi would really arrive in Taipei, how Chinese military would respond, and what such a visit might mean at a time of already strained US-China relations.

Shortly after Pelosi arrived, online livestreams covering the event stopped, and the local servers for China’s leading social media platform Weibo temporarily went down. The sense of anticipation that had dominated Weibo turned into sudden anger and frustration.

Chinese officials had repeatedly warned that China would not “sit idly by” if Pelosi visited. One of China’s top political commentators, Hu Xijin, had even suggested that if US fighter jets escorted Pelosi’s plane into Taiwan, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) would have the right to forcibly dispel or even shoot down Pelosi’s plane and the jets. Yet nothing prevented Pelosi and her team from safely arriving in Taiwan. “Even our community guard who makes 1500 [US$220] a month does a better job; if he says you can’t come in, you can’t come in,” one Weibo user wrote.

In dominant narratives on Chinese social media regarding the developments in Taiwan, the United States is depicted as an evil force meddling in China’s affairs and China as the “wolf warrior” protecting the territorial integrity of the nation.

But sentiments shifted on 3 August when China’s propaganda machine started running at full speed. Chinese state media suggested that Pelosi’s visit was a strategic act by the United States to meddle in Chinese internal affairs and heighten cross-Strait tensions. State broadcaster CCTV called the move a “road to ruin” and published an online post showing the characters for “China” with the middle stroke of the first character representing the number one. “In this world there is only one China,” the slogan said. “The Motherland must be reunited, and it inevitably will be reunited,” the Chinese Communist Party-aligned newspaper People’s Daily wrote on Weibo.

A Chinese government white paper published this month also reiterates that Taiwan is indisputably a part of China and that “complete” reunification will be realised regardless of any attempts by “separatist forces” to prevent it.

A new wave of national pride and expressions of nationalism flooded social media after China announced countermeasures in response to Pelosi’s visit and began live-fire military drills around Taiwan.

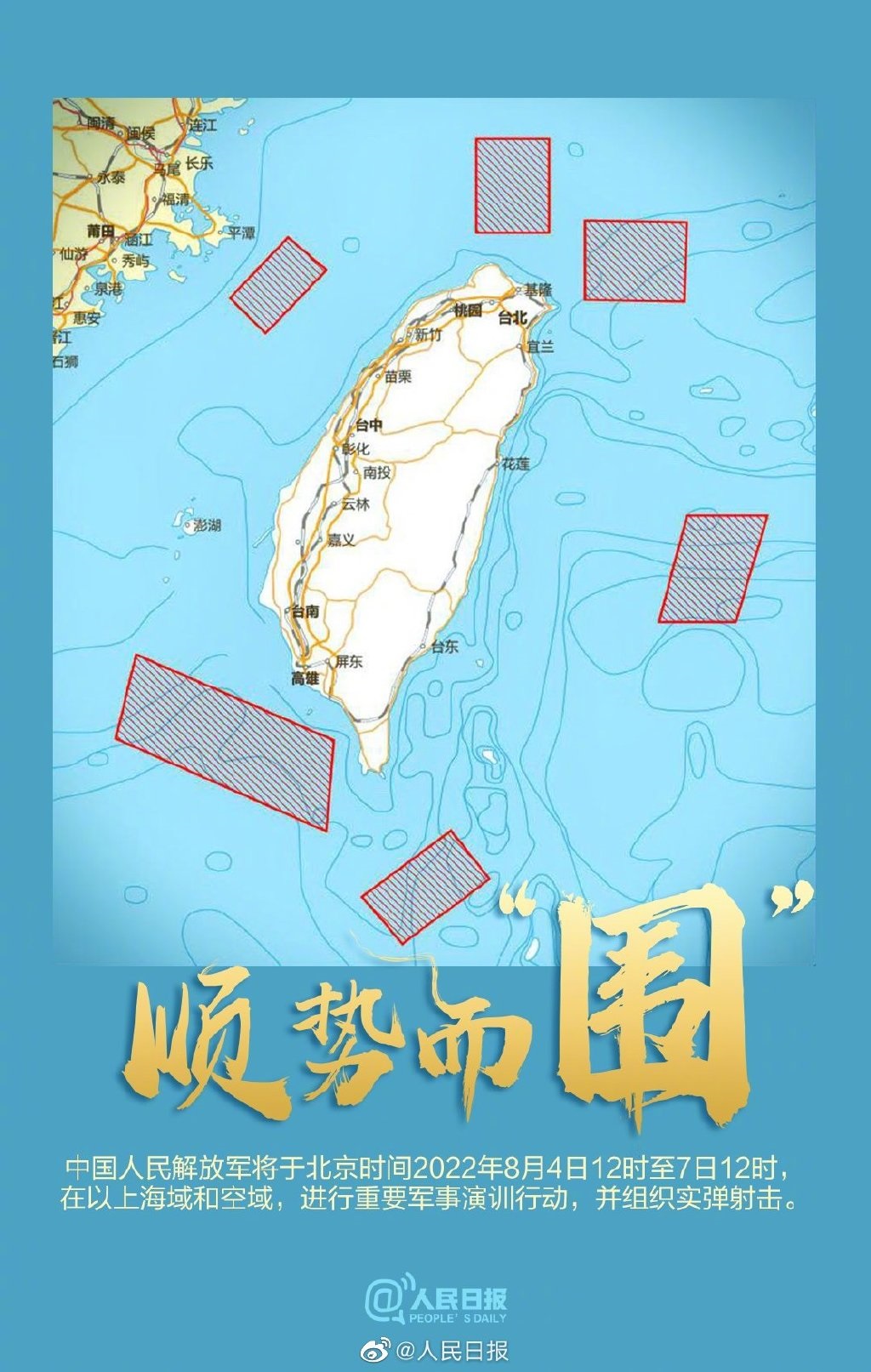

“It’s begun!” People’s Daily announced on 4 August, posting an image with the slogan: “Seize the momentum to ‘surround.’” The move was applauded, with more than 115,000 likes on the post, many expressing pride in China’s “strikeback”. A typical comment said: “I believe in our motherland, I support our motherland.”

Various official military accounts, such as that of the Eastern Theatre Command (one of the five theatre commands of the PLA), frequently post action-packed short videos featuring cinematic music, Chinese military staff preparing for action, and military aircraft and vessels conducting exercises around the island of Taiwan. Although the most recent military exercises were initially intended to continue until 7 August, China’s military announced new exercises around Taiwan on 8 August, followed by another round after a second US delegation visited Taiwan on 15 August.

Over the past two weeks, Chinese social media have become a visual battlefield. Dramatic spectacles disseminated by the government are instrumental in winning the hearts and minds of the Chinese people, while also being used as a symbol of power to intimidate so-called “separatist forces” and show off China’s military rise to the international community.

In The Camera at War, Mette Mortensen, who researches media and conflict, argues that digital visual culture has become increasingly relevant as a part of warfare, not just for recording unfolding events, but as a forceful weapon to guide public opinion and affect political debate.

The spectacle surrounding the Taiwan military exercises is by no means a one-dimensional media effort, but instead a dynamic one where state-led propaganda and grassroots nationalism meet. From TikTok to Weibo, China’s state media channels, official accounts, military bloggers, online influencers and regular online citizens engage in a collective effort to record, edit, dramatise and share the sometimes movie-like videos showing large-scale military exercises, including live-fire drills, naval deployments and ballistic missile launches.

From Fujian’s Pingtan Island, one of mainland China’s closest points to Taiwan, residents and tourists post videos of their front-row perspective of projectiles launched by the Chinese military and helicopters flying past. “I’m jealous of their view!” Chinese online users responded, with many sharing the “stunning scenes” of large-scale exercises that could be seen from the island.

This week, the Eastern Theatre Command also released a music video showing bursts of military drills, including the firing of missiles, while men sing: “Just waiting to be summoned … towards victory, no surrender, we vow to defend every river and mountain within our motherland.”

Among hundreds of comments, there are many patriotic posters hoping that the developments will become more than mere spectacle: “We’re fired up,” one popular Weibo comment said: “Sooner or later, we’ll reunify.”