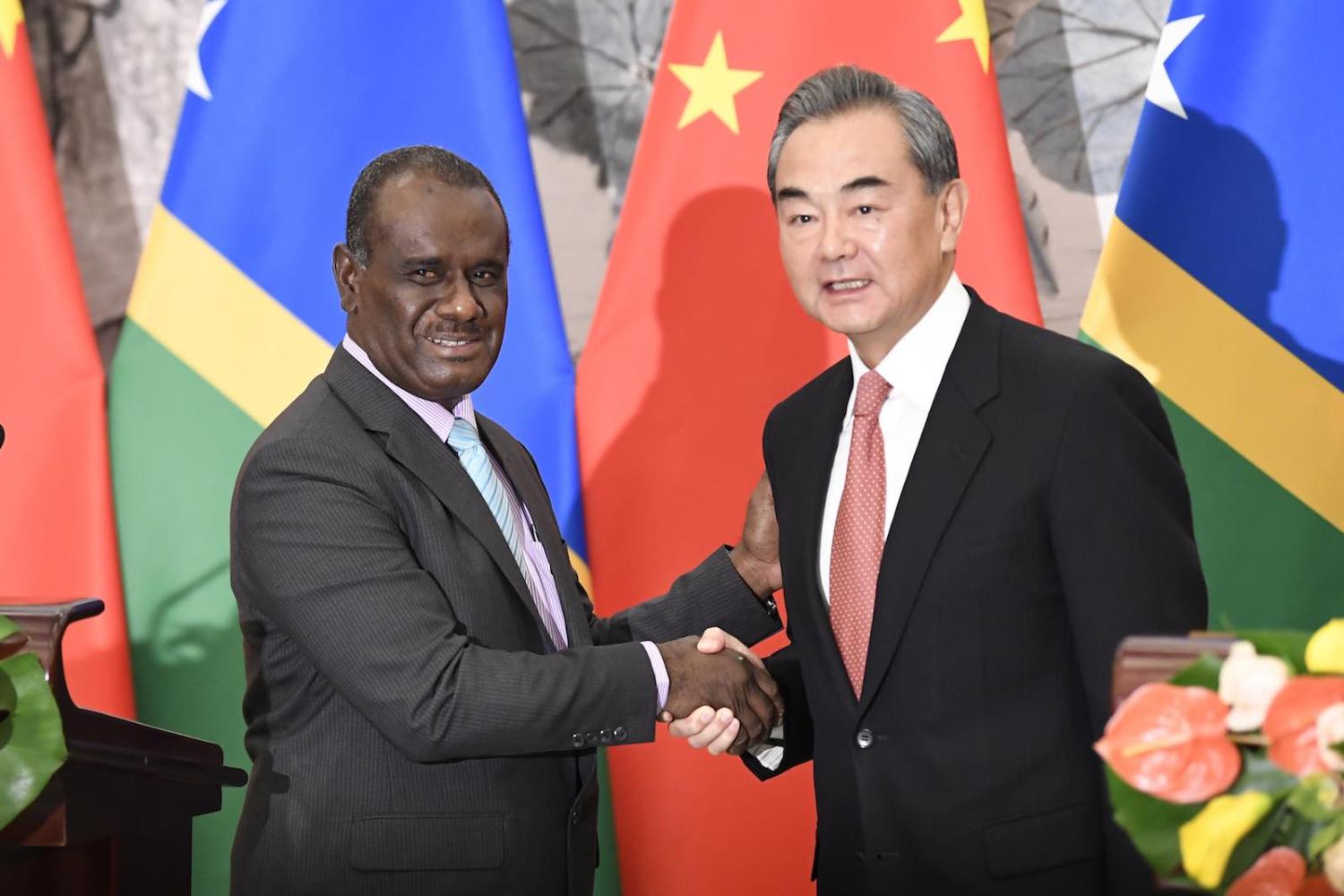

After a public, protracted, and somewhat torturous process, the government of Solomon Islands last week decided to sever ties with Taiwan in favour of the People’s Republic of China. Days later, in sharp juxtaposition, Kiribati suddenly broke ties with Taiwan too, catching everyone by surprise. Taiwan’s support from Pacific countries was reduced by one-third in just a few short days, demonstrating China’s resolve to marginalise Taiwan diplomatically.

With their combined population outstripping Taiwan’s remaining supporters in the Pacific more than sevenfold, Kiribati and Solomon Islands are a major prize for China. The sixth and seventh nations to swap allegiance since Tsai Ing-wen was elected in January 2016 leave Taiwan with just 15 remaining diplomatic allies globally.

Surprisingly, we have heard little about what kind of package was on offer to either country to induce a swap. One would expect it to be lucrative, as this is not a card the government can play again.

For Taiwan this is a blow, although not a fatal one. Its diplomatic network helps to give it a voice and some legitimacy in multilateral organisations, such as the United Nations, where it is shunned. But the network is largely a symbolic one. No one is under any illusion that if push came to shove these allies could do anything to help Taiwan beyond condemnation of China. A look at UN voting patterns indicates that even support from these allies is not always guaranteed.

Military ties, particularly with the United States, are far more important for Taiwan’s enduring sovereignty. Some, including the Taiwanese government, argue that China is ramping up pressure on the diplomatic network to sway next January’s closely contested elections. But the aid spending required to maintain Taiwan’s diplomatic network is not popular in Taiwan, and whatever influence it may be having is surely being undone by the unrest in Hong Kong.

Kiribati and Solomon Islands help solidify China’s narrative of its emergence as a major player in the Pacific. There was already a sizeable Chinese commercial presence in Solomon Islands. China is the small nation’s largest export partner, thanks to the largely unregulated logging and more nascent mining industries. It is also a growing source of imports, as more and more Chinese trade stores pop up all around the country. The story is similar in Kiribati, where China has taken a particularly keen interest in accessing the small nation’s bountiful fisheries. Now that diplomatic ties are following these strong commercial links, we are likely to see further anxiety about how China might seek to increase its influence.

How China will choose to engage with Kiribati and Solomon Islands, and how it may aim to benefit strategically from this new relationship, will keep analysts in Canberra busy. But it does not dramatically change the calculations with regard to Australia’s relationship with the region, and in particular Solomon Islands.

Australia has an outsize role in Solomon Islands, one of our closest neighbours. Since leading the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI) in 2003, Australia has been instrumental in helping the nation get back on its feet after a breakdown in law and order. Pouring in more than $3 billion in aid since then, and close to $200 million in 2018–19, Australia has a vested interest in Solomon Islands’ long-term stability and prosperity. Prime Minister Morrison was right to say on his visit to Solomon Islands in June that the question of recognition for Beijing was a sovereign matter, and Australia didn’t have a horse in this race. Any other response would have been hypocritical, given that Australia recognises China, and the bigger picture is far more important. While the swaps may make navigating bilateral relationships with Kiribati and Solomon Islands trickier, it is a manageable issue not worth wasting political capital on.

For the United States, the calculation is quite different. Because its interests have been so aligned with Australia’s, the United States has been happy to leave things to Canberra, allowing its bilateral engagement to dwindle to nearly nothing, including the closing of the US embassy in Solomon Islands. Australia’s stance here highlighted a divergence of interests, and while the US has been scrambling to reengage, it has been too little too late for a country with such a large legacy in Solomon Islands from the Second World War.

Turning back to the region. The dominos look to have stopped falling for now, with the four remaining Taiwan allies appearing to hold. Beyond a few (likely relieved and exhausted) Taiwanese diplomats jumping on a plane, not much will have changed from day to day. For the politicians of Kiribati and Solomon Islands, this was not a foreign-policy calculation, but an economic one. They have very little international leverage and are surely betting the switch will gain them more support through foreign aid and other economic incentives.

Surprisingly, we have heard little about what kind of package was on offer to either country to induce a swap. One would expect it to be lucrative, as this is not a card the government can play again. Not publicising the details raises questions about what happened under the table and will make it harder to hold China accountable down the road.

In the medium to long term, the swap will open the door even wider for Chinese enterprise to engage, something the governments may not be ready to manage. Much of this engagement was going to happen anyway, but at least now Kiribati and Solomon Islands will have officials in-country to whom they can air their grievances.

For the people of Solomon Islands in particular, the decision must come with a sigh of relief. The debate has consumed a huge amount of parliamentary bandwidth since the April elections. With business sentiment, the budget, and the economy all looking pretty flat, the hope is that the government can now get back to work on domestic issues.

For all that it may have offered as a part of this diplomatic dance, having China as a diplomatic partner will not profoundly change either country’s economic or social challenges, which are far larger challenges for the governments to tackle.