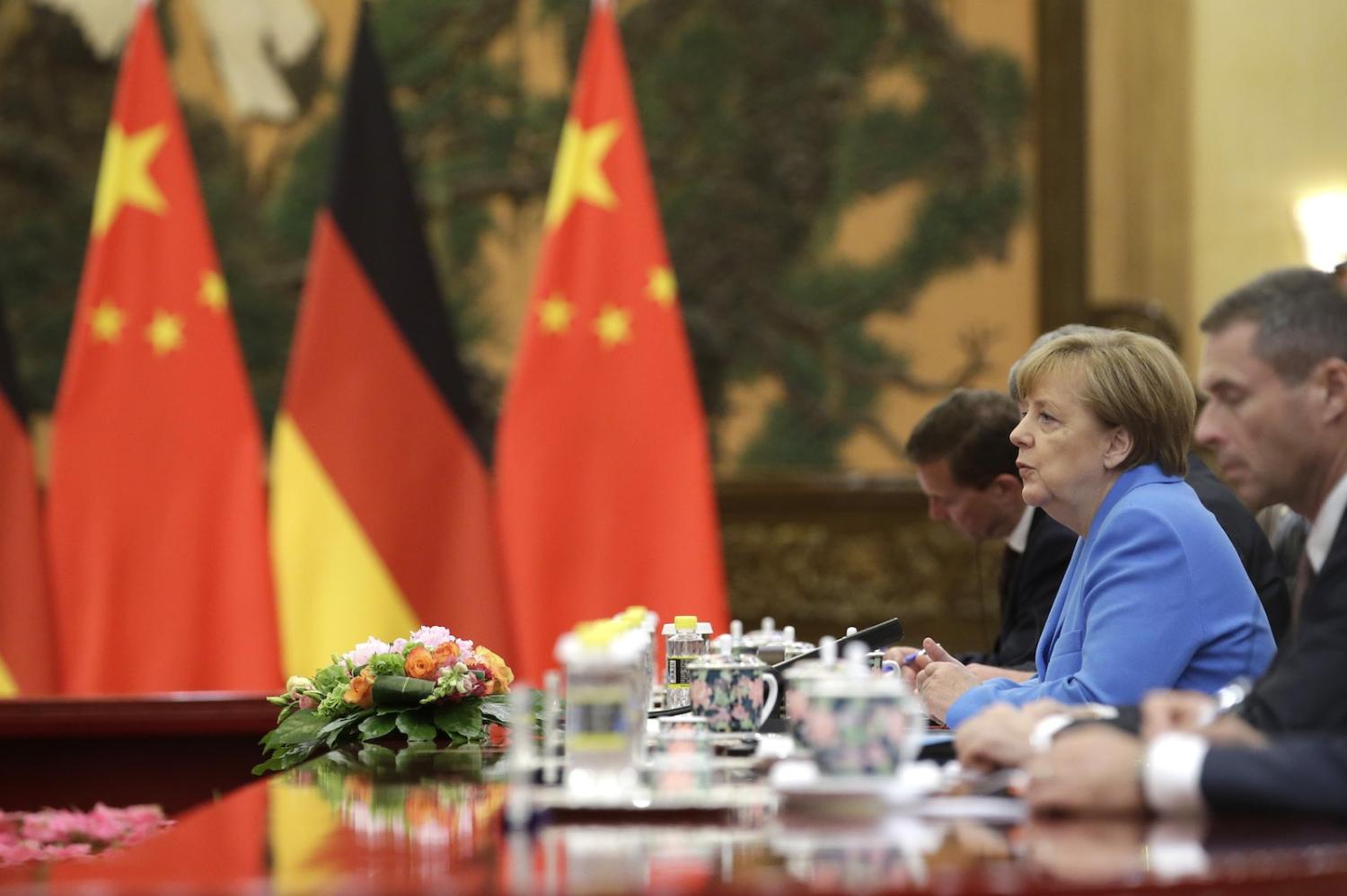

Until recently, Germany was one of the few major Western countries that China had consistently amicable relations with in an increasingly hostile international environment for Beijing’s export-oriented industries and foreign investments. Germany, China’s fourth-largest trade partner, did not join US President Donald Trump in his blistering condemnation of Beijing’s trade and investment practices or its geopolitical ambitions in East Asia. Instead, Berlin frequently closed ranks with Beijing in condemning US threats of tariffs, sanctions, and trade wars.

In recent times Berlin has sent out discreet but increasingly explicit signals of frustration about China’s economic practices.

But in recent times Berlin has sent out discreet but increasingly explicit signals of frustration about China’s economic practices, showing that despite their wariness of Trump’s economic collision course, German officials and business representatives ultimately share many of Trump’s fundamental criticisms of Beijing.

Leading German business associations and economic research institutes that had previously refrained from explicitly criticising Beijing have begun to advocate harsh economic measures against China. A particularly noteworthy case is that of the Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie (BDI), Germany’s most powerful industrial lobby organization which represents more than 100,000 companies and has regular access to top German policymakers. In January 2019, the BDI raised eyebrows when it published a strategy paper that asked the German government and the EU Commission to sharpen their economic instruments in the “contest of economic systems” with China’s “state capitalism” and to put more pressure on Beijing.

The BDI paper accused China of distorting markets and prices through state intervention, resulting in worldwide overcapacities in sectors such as steel production, and it claimed that the same would soon be the case in high-technology sectors like robotics and battery production. The paper made 54 concrete policy demands, including a strengthening of EU anti-subsidy instruments to check and, if necessary, prevent state-sponsored foreign acquisitions of European technology companies.

The BDI expressed particular concern about the fact that, while China has been able to forge massive global corporations through government intervention and support, mergers of large companies in Europe are blocked by restrictive EU anti-trust legislation. It suggested that market forces should be permitted to form large-scale “European champions” among industry corporations.

This marked the first time a major German business association has used such unequivocal and confrontational rhetoric to criticise Beijing’s industrial policy. The BDI’s main propositions were subsequently adopted by German Minister of Economics Peter Altmaier in his response to the European Commission’s rejection, in early February, of the planned merger between two of Europe’s largest railcar corporations – Germany’s Siemens and France’s Alstom – on anti-trust grounds. Both companies regarded the merger as an important step to counter growing competition from railcar companies in China, particularly the China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation (CRRC).

Altmaier, one of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s closest confidants in the governing party CDU and the former head of her Federal Chancellery, later presented the draft for a “National Industry Strategy 2030” – a large-scale macroeconomic planning reform aimed at boosting Germany’s industrial sector and increasing its technological competitiveness, particularly vis-à-vis China.

The plan marked a shift in Germany’s industrial policy and drew immediate criticism from opposition politicians and economists, accusing Altmaier of protectionism and intrusive state intervention, even likening his ideas to China’s own economic planning. But an equally large number of prominent economists and industrialists have defended the plan, usually with reference to the threat of rising Chinese competition.

Germany has gone further in what presumptive future German chancellor Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer recently claimed is a “contest of systems” between Europe and China. Another controversy erupted over the strengthening of foreign investment controls, amid growing concerns about Chinese investments in strategic sectors of the German economy. In December, new investment screening rules were agreed which stipulate that, in “security-relevant sectors” of the economy such as defence, food production, and a very wide range of “critical infrastructures”, the German government can review and withhold approval for any transaction in which a foreign (non-EU) investor plans to buy more than 10% of a German company (previously the threshold had been 25%). Most observers agree that this measure was primarily directed against China and was prompted by previous controversies surrounding state-mandated Chinese investments or investment attempts in German high-tech companies, such as the industrial robot producer Kuka, the energy provider 50Hertz, or the semiconductor producer Aixtron.

High-profile corporate takeovers by state-backed Chinese companies had initially been observed with cautious optimism in Germany, but more recently some of these new Sino-German corporate partnerships in the high-tech sector, including the robotics company Kuka and the automobile supplier Grammer, have turned sour in the wake of forced management restructurings and the Chinese investors’ assumption of greater control over the companies’ day-to-day business operations.

Chinese electronics giant Huawei has also been in the spotlight, with concerns about potential political espionage, subversive activities, and foreign interference in critical national infrastructure. In late January, the major German intelligence and security agencies recommended to exclude Huawei technology from the planned construction of the new 5G telecommunications network, lest the Chinese government could use it for espionage and surveillance purposes, or even to install hidden ‘kill switches’ that could hypothetically disable large parts of Germany’s critical infrastructure in the future.

It is increasingly clear that Germany’s decades-long (and exceptionally lucrative) economic romance with China is now plagued by wariness, suspicion, and a sense of fierce competition – a point also underscored by Berlin’s growing aversion to Chinese economic activities in Southern and Eastern Europe.

Having eschewed confrontation for years, Germany now finds itself at a crossroads in its economic relations with China and the mood in Berlin has undoubtedly swung against Beijing.