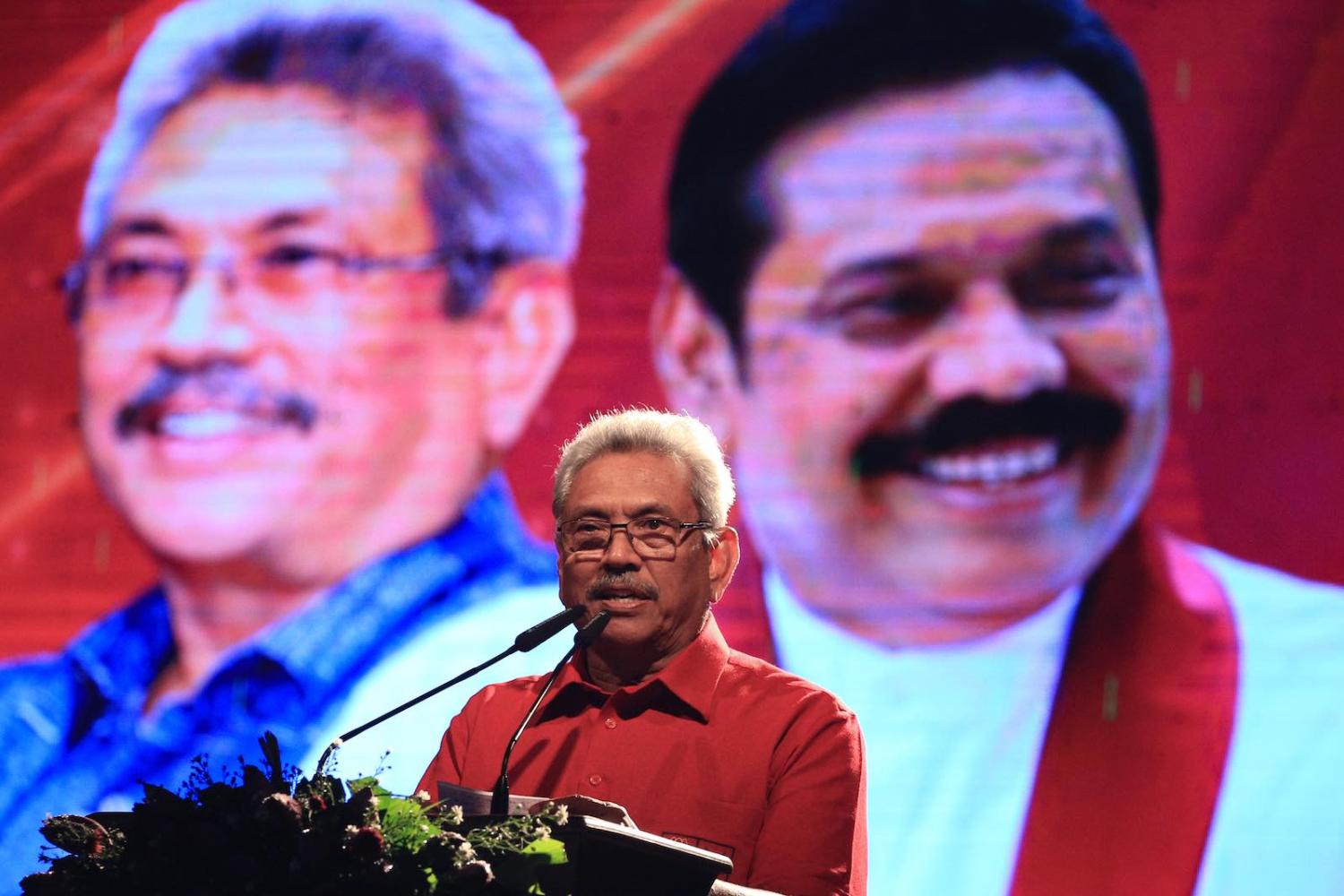

Gotabaya Rajapaksa was sworn in as president of Sri Lanka on 18 November. He served as secretary to the ministry of defense when his brother, Mahinda Rajapaksa, ruled the country, from 2005 to 2015. The Rajapaksas are inveterate authoritarians, and the country is about to take a troubling, undemocratic turn.

Sri Lanka doesn’t have reliable public polling, although Rajapaksa was widely perceived to be the favorite in this contest. He won 52 percent of the vote and Sajith Premadasa captured 42 percent.

This election was mainly about national security, Sinhalese Buddhist nationalism (ethnic Sinhalese are the majority community), economic issues, and the failures of the previous government. The Easter bombings solidified the electorate’s desire for stronger and more decisive leadership. Going forward, the space for dissent in Sri Lanka is expected to shrink – and quickly.

The Rajapaksas are neither viscerally anti-American nor reflexively pro-China. They would have no problem establishing cordial ties with Washington, particularly now – given Donald Trump’s propensity to praise autocrats and downplay international human rights issues.

The last time the Rajapaksas were in power, they put the country on a dictatorial path. Abductions were a problem. Human rights violations were widespread. Power continued to be centralized. All these Rajapaksa hallmarks are expected to resume imminently.

Nonetheless, we’ll have to wait and see how the country’s new president leads and how his relationship with his older brother evolves. Mahinda Rajapaksa has already been appointed prime minister. Another brother, Chamal Rajapaksa, is a cabinet minister. It’s not known how power will be shared among the family, or how decisions will be made by the Rajapaksa administration 2.0.

On the foreign policy front, this Rajapaksa administration may be different from the previous one. A lot of ink has been spilled about the geopolitical angle to the Rajapaksas’ return. Historically, Sri Lanka has followed a foreign policy of nonalignment.

However, when Mahinda Rajapaksa was president, the island nation became increasingly close to China, and many commentators have claimed that a Rajapaksa redux means that Sri Lanka would again align itself closely with Beijing. The reality is more complicated.

During the end of the civil war and beyond, the Rajapaksas embraced the Chinese largely because they were turned away by the US and its allies. This fraying of ties was due principally to egregious human rights violations committed during and after the war. Both Mahinda and Gotabaya Rajapaksa are alleged war criminals.

Sri Lanka’s new president gave up his US citizenship to contest for the presidency. Another brother, Basil Rajapaksa, who was heavily involved in the presidential campaign, remains an American citizen. The Guardian notes that he “will continue to play a powerful role behind the scenes as chief strategist”.

The Rajapaksas are neither viscerally anti-American nor reflexively pro-China. They would have no problem establishing cordial ties with Washington, particularly now – given Donald Trump’s propensity to praise autocrats and downplay international human rights issues. Besides, a major lesson from Mahinda Rajapaksa’s decade as president is that it behooves a small country like Sri Lanka to pursue a more balanced foreign policy.

The last time the Rajapaksas were in power, they systematically put Sri Lanka’s messy democracy on life support. It won’t be surprising if the current Rajapaksa administration produces similar results, or worse.