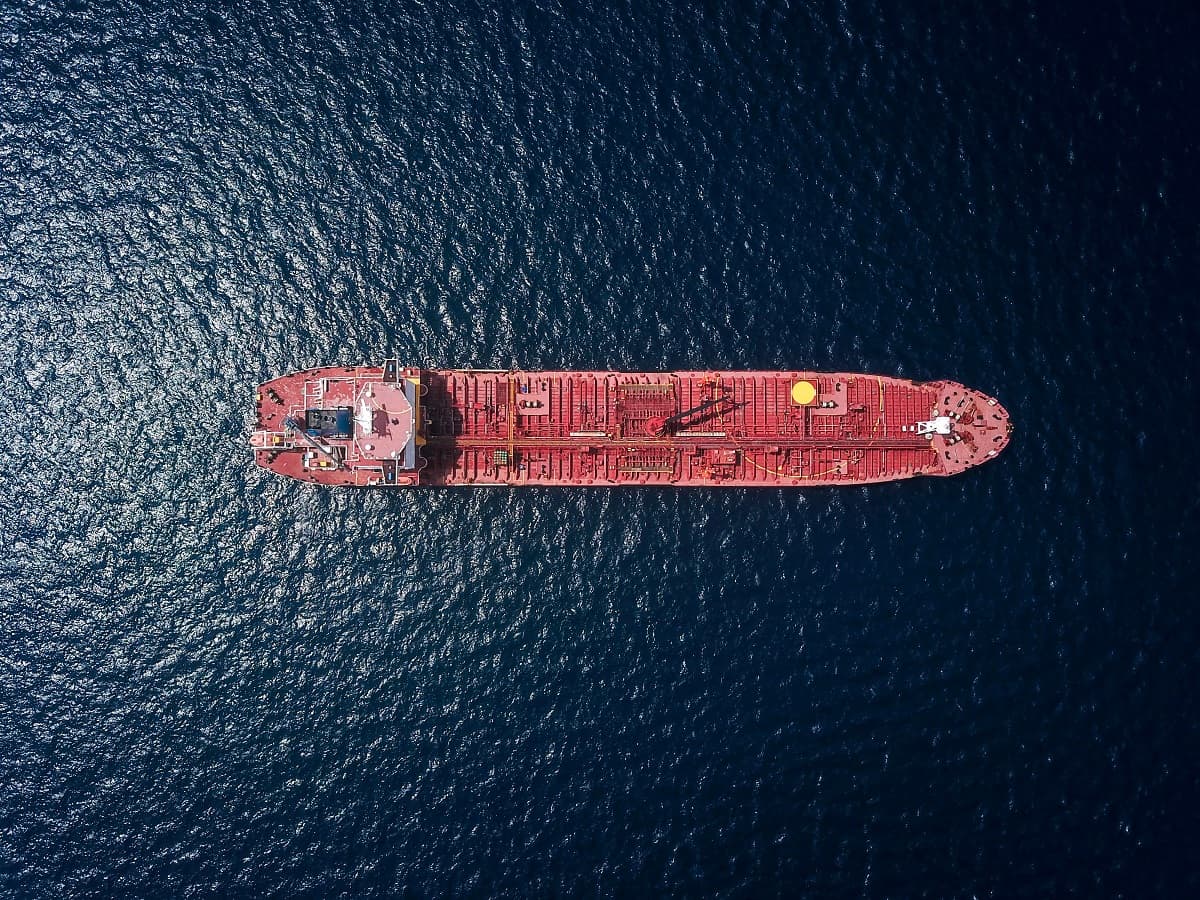

The two giant freighters floated “dark” in the open ocean not far from Indonesia. Their positioning transponders switched off, neither tanker displayed a national flag – but one ship was known to have claimed Iranian registration, the other to have made at least eight visits to Venezuela in recent years.

And between them pumped thousands of barrels of oil.

In July this year, Indonesian authorities intervened in this ship-to-ship oil transfer being carried out within Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). With assistance from Malaysia, one ship was seized, Arman 114, a tanker claiming Iranian flag registration. However, the tanker known as S Tinos, also referred to as Lilu, and found to be Cameroon-flagged, managed to escape. Neither tanker had submitted a ship-to-ship oil transfer plan to the Indonesian authorities, as required by Indonesian law and the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution by Ships (MARPOL).

This scenario presents a classic case of “dark ships” used in schemes to circumvent rules or sanctions. While the act of ships going “dark” by disabling their Automatic Identification Systems constitutes a direct breach of the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), it does not necessarily confer enforcement power upon coastal states, as the flag state maintains exclusive jurisdiction and control over the safety features of the vessels.

So, the case raises a fascinating question about whether Indonesia, in its capacity as the coastal state in this case, had the jurisdiction to seize the tankers?

The incident under scrutiny involves a “ship-to-ship transfer”, which refers to the transfer of cargo between two seagoing vessels, as opposed to “offshore bunkering”, which entails refuelling another vessel’s fuel bunkers to power its engines. Unlike offshore bunkering, a ship-to-ship transfer within an EEZ is arguably an activity in relation to which the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) does not explicitly allocate rights or jurisdiction to either the coastal state or other states (Article 59 of UNCLOS).

If both tankers had been flying a flag, the assessment would centre around establishing which state holds jurisdiction over the EEZ ship-to-ship oil transfer: the flag state or the coastal state. Yet, this scenario was irrelevant. This is because both tankers can be assimilated to vessels without a nationality (stateless vessels) due to their failure to display a national flag. This stateless classification applies not only to vessels that fly no flag, but also to those bearing fraudulent or multiple registries.

Under UNCLOS, the primary responsibility for the implementation of international standards and regulations pertaining to ships rests with the flag state. Upon registration, a ship is entitled to fly the flag of the corresponding state (flag state), thus placing itself under the jurisdiction of that state. In cases where ships lack a nationality or are assimilated to stateless vessels, they forfeit the ability to claim the protection of any state (Article 92(2) UNCLOS).

Furthermore, a crucial aspect of this case is the reported occurrence of an oil spill when both tankers attempted to escape into Malaysian waters. While the exact spill location remains unclear, it is likely that the incident occurred within Indonesia’s EEZ, given the tankers’ attempt to flee amid ongoing oil transfers. The hurried escape led to the detachment of the hose connecting the two tankers, resulting in the spill.

In standard situations involving duly registered foreign vessels, coastal states have limited enforcement jurisdiction over pollution originating from ships within their EEZ. This is because UNCLOS upholds the primacy of enforcement jurisdiction by the flag state (Article 228(1) of UNCLOS).

UNCLOS sets some high thresholds to safeguard foreign ships from coastal state enforcement jurisdiction pertaining to ship-source pollution in the coastal state’s EEZ. Coastal states must suspend their own proceedings and transfer the case to the flag state if the flag state initiates proceedings within specified time frames (Articles 4(1), 4(2), 6(4) of MARPOL, and Article 228 of UNCLOS). This is unless there exists “clear objective evidence” of “major damage” or a “threat of major damage” to the coastal state’s interests or fisheries resources (Article 220(6) of UNCLOS, and Article 2 of MARPOL).

However, since the two tankers can be assimilated to stateless vessels, the restrictions on the enforcement jurisdiction of coastal states over such ships might not be applicable. Consequently, Indonesia as the coastal state could seize and initiate legal proceedings against them. Any penalties imposed by Indonesia would be confined to monetary penalties (Article 230(1) of UNCLOS).

Finally, despite reports that Arman 114 left Iran’s Qeshm and Larak Islands in June 2023, carrying around 1.9 million barrels of crude oil following multiple ship-to-ship (STS) operations, Iran’s oil ministry has denied any connection between this cargo and Iran. While Iran disclaims ownership of the cargo, some might argue that Iran has not explicitly denied Arman 114’s registration under the Iranian flag.

In a scenario where Iran does not contest Arman 114’s Iranian flag status, the fact that both Iran and Indonesia are parties to Annex I of MARPOL becomes pivotal. This annex pertains to the prevention of oil pollution, both from operational measures and accidental discharges from ships, including those occurring during ship-to-ship transfers of oil cargo between oil tankers at sea. Under MARPOL, state parties are obliged to prohibit violations and establish appropriate penalties for any MARPOL violations occurring within their jurisdiction (Article 4(2) of MARPOL).

In accordance with MARPOL, Indonesian law requires oil tankers seeking to conduct ship-to-ship operations in Indonesia’s EEZ to provide advance notification. While MARPOL requires 48 hours' notice (Regulation 42 of MARPOL Annex I), Indonesia mandates a shorter 24-hour notice (Article 6(8) of Transport Minister Regulation No. PM 29 of 2014).

Additionally, Indonesian law requires that oil tankers engaged in ship-to-ship operations must carry an approved plan detailing the procedures, which must be endorsed by the country’s Transport Ministry (Directorate General of Sea Transportation). Moreover, these vessels are also obligated to document and maintain records of each ship-to-ship operation for a three-year period onboard (Regulation 41(1) of MARPOL Annex I; Article 6(8) of Transport Minister Regulation No. PM 29 of 2014).

Indonesia may retain the option to initiate legal proceedings against the tanker by asserting that the oil spill resulting from the ship-to-ship operations poses a “threat of major damage” to Indonesia’s interests and fisheries resources (Article 220(6) of UNCLOS and Article 2 of MARPOL). If this argument falls short, the enforcement power would remain with the flag state. It means that Iran could institute proceedings within a six-month window to address the violations of its tanker (Article 228 of UNCLOS), and Indonesia would be required to provide Iran with pertinent information and evidence regarding the tanker’s violations of MARPOL (Article 4(2) of MARPOL). If Iran refrains from exercising its enforcement jurisdiction, Indonesia as the coastal state can pursue legal action against the tanker. This course of action would come with the obligation of notifying both Iran and the International Maritime Organisation about any measures or proceedings taken in response to the tanker’s MARPOL violations.