Syria is one among several Middle East regimes which believe that repression, if not used in moderation, provides a necessary answer to challenges to the existing political and social order. Accordingly, Western governments have to decide the relationship they wish to have with Syria, and its neighbours and friends, including Iran – and how they wish their values to be reflected in their approaches to that relationship.

Understanding the consequences of the Syrian tragedy for our interests should lead us to support carefully calibrated re-engagement with the Assad regime. The alternatives are worse.

Without respect for principles and institutions of international humanitarian law, and efforts to hold accountable those who breach them, predictable and constructive dealings between states and the harnessing of human potential are hardly possible. An absence of respect for those principles, both domestically and in dealings between states – and the weakening of political will to defend robustly the values of political liberalism and the moral authority of international norms and values – brings us closer to the scourge of war.

But in the case of Syria, behind that self-evident truth are complex political and moral issues.

If concerns exist at all in Damascus for the absence of accountability for brutality in the name of security, or for the opportunities for recruitment and indoctrination afforded by burgeoning prison environments, torture, and other abuses, they are seen as issues of a lower order than the immediate need to preserve the identity and essential character of the state itself.

Advocacy for human rights must be framed within a realistic acceptance that any return to effective political leadership will have to come about within the existing power structure.

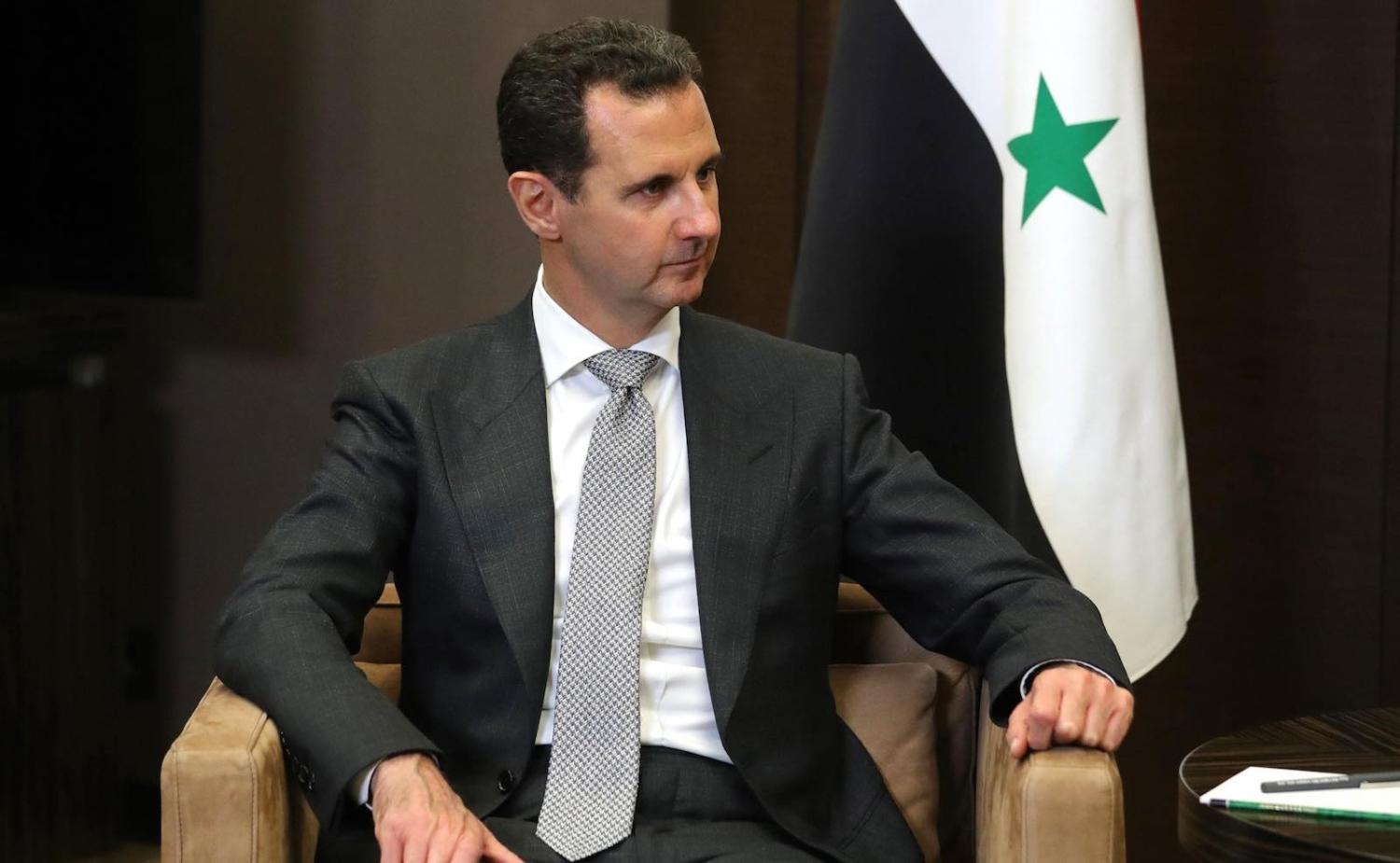

Bashar al-Assad, like his father before him, proved determined to avoid the asking of open-ended questions about the appropriate relationship in Syria between state and society. Meanwhile, the ideological disposition of opposition groups was reduced from mid-2011 to an Islamist-inspired rejection of the existing social and political order.

Whether responsibility for the human tragedy of Syria rests mainly with the Syrian regime, other governments, or non-state actors, it is the Syrian poor, and the marginalised, who have been demonised, dehumanised, and exploited. And the values that best protect Australia’s interests at the global level have suffered as respect for international law has been set aside by the parties to the conflict.

The challenge is to find an acceptable balance between upholding core principles of international humanitarian law in the Syrian context, and recognition that without a return to economic growth and security, those principles, however worthy we may consider them to be, will matter little to those Syrians who are most vulnerable.

The application of economic sanctions to Syria – in practice, a manifestly inhumane, ineffective, and altogether despicable assault on the most vulnerable elements of Syrian society – add to the challenges ahead.

There is no chance of security or durable progress in Syria without economic advancement. The opportunity costs, in terms of wasted human potential, corruption, and human rights abuses associated with repression, insecurity, and conflict all weigh heavily against the likelihood of achieving levels of balanced economic performance that can restore infrastructure and human capital and combat Syria’s growing ecological threats and food and water insecurity.

But in Syria, and elsewhere in the region, advocacy for human rights must be framed within a realistic acceptance that any return to effective political leadership will have to come about within the existing power structure. A leadership that has proven willing to see the death and displacement of so many of its own citizens is not going to relinquish or genuinely share political power beyond its immediate base.

The incremental advancement in Syria of empowerment, within the rule of law, at all levels, from the state to the society to the household, is as desirable and yet as remote a prospect as ending abuses of human rights. And remaking Syria – or Yemen or Libya – for the benefit of their citizens may not be possible without remaking the wider Middle East.

History suggests that is something to which the rest of the world is unlikely to make a positive contribution. And words of sound and fury delivered in multilateral forums will make little difference in practice to Syrian behaviour.

But if we wish our values to be respected among future generations of Syrians, and elsewhere in the region and beyond, we should be prepared to stand up for those values by using such political, diplomatic, and intellectual leverage as may be available to us. And we should be prepared to take a long-term view of what is required.

Syria, not unreasonably, sees itself as deserving of international recognition as a country of substance and importance in the Arab and regional context. The ending of its isolation from the international community is important to it.

Calibrated, strategically planned re-engagement, in consultation with Western and Arab partners, offers the most likely path to seeing a Syria emerge which, like Tunisia, chooses to benchmark its achievements as an Arab state against contemporary ideas among a younger generation, in Syria and within the wider Arab world, of what it means to be Arab and “modern”. And it is among those ideas of what modernity looks like that the norms and institutions of international law are most likely to be respected.

The extent and timing of steps to help Syria move in that direction may depend, in practice, on a parallel process of realignment of dealings between Washington and Tehran. There must be some semblance of respect for the dignity and rights of its ordinary citizens if re-engagement with Western countries is to proceed. Russian sensitivities would need to be handled with particular care. But there is a strong case, humanitarian, diplomatic, and otherwise, for further exploration of the limits to the possible.

For their part, Western governments will see their interests served best, not by ongoing insecurity and conflict and the imposition of collective punishment in Syria, but by the re-emergence, over time, of a Syria that is once again confident, economically dynamic, socially progressive, and respected within the region.