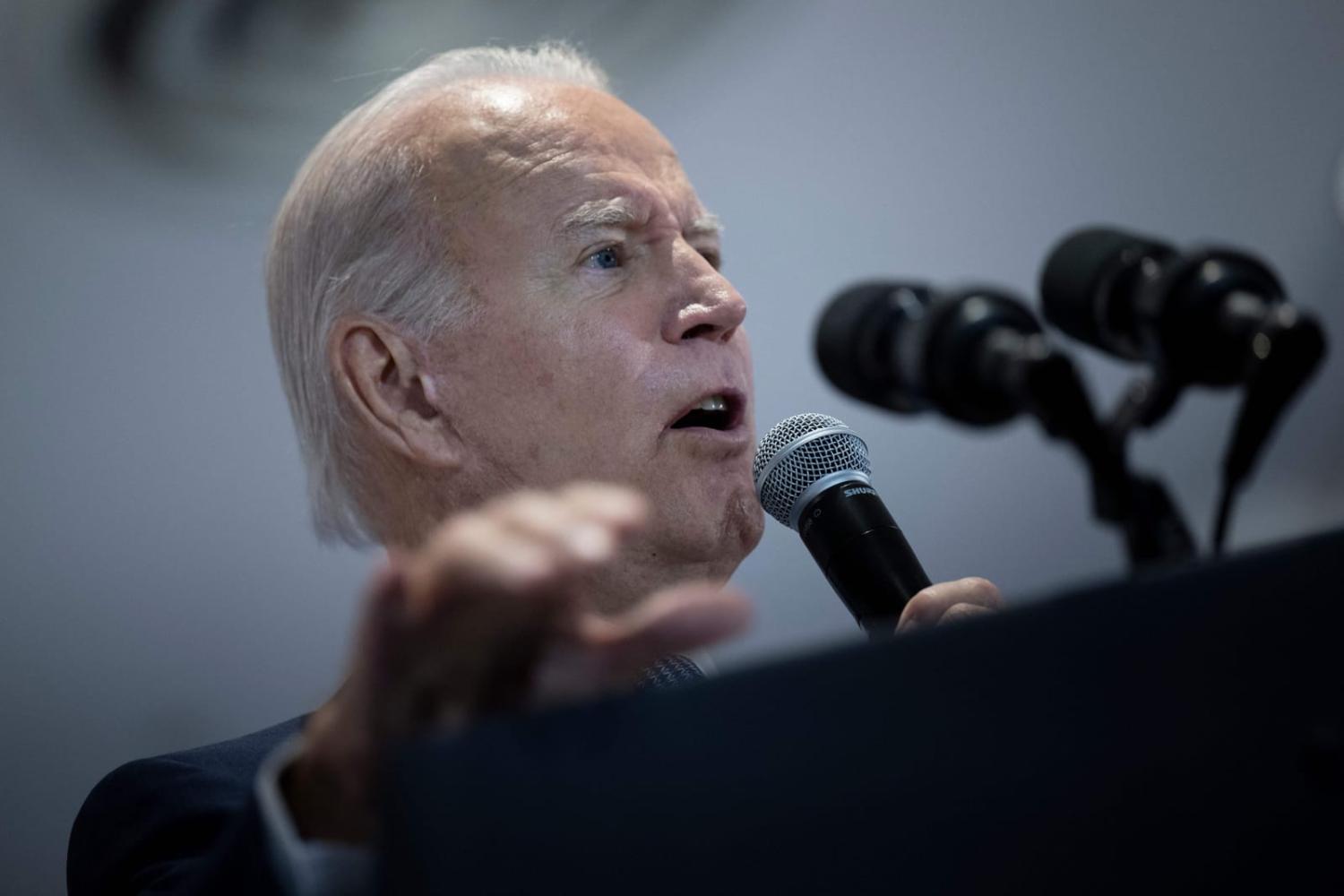

The more often US President Joe Biden appears to abandon strategic ambiguity by saying quite clearly that America would go to war with China to defend Taiwan, the more difficult it becomes to dismiss what he says as a presidential fumble. That was not at all difficult the first time, especially when the White House moved so swiftly to affirm the US policy had not changed. It was harder to do the second and third times, because with each recurrence it became less plausible that Biden would continue to be so muddled on an issue of such importance. But it also seemed unlikely that the President would deliberately set himself up to be humiliatingly corrected by his own officials, as he was on each occasion when the White House issued the same “clarification”.

Now, with the fourth repetition, the “fumble” explanation has become frankly implausible, and we must tentatively conclude that the Biden administration has changed its declaratory policy on what is, perhaps, the most important foreign-policy question in the world today. They have half-abandoned the old policy by having Biden say one thing and his officials say another. They are deliberately creating ambiguity about whether strategic ambiguity is or is not still their policy. And they may even be calculatingly exploiting age-related doubts about the President’s mental acuity to do it.

That is surely unprecedented.

Yet one can see why they might do it, because they do have a problem. The old policy of strategic ambiguity was sufficient to deter Beijing back in the days when America’s military superiority was unchallenged. But the further the military balance has shifted China’s way, and the higher the costs and risks to Washington of defending Taiwan, the harder it has become to convince Beijing that America would intervene. That has made it more important to unambiguously declare America’s determination to do so, if China is to be deterred from attacking Taiwan.

Growing recognition of this problem has led to a lively debate in Washington in recent times. Influential figures in Congress and the think tanks have argued that strategic ambiguity should be abandoned in favour of the kind of unambiguous declarations that Biden has now got into the habit of making. And the more aggressive China’s conduct towards Taiwan has become the more compelling those arguments have been.

But the counter-arguments are strong, too. America’s position of strategic ambiguity is an integral part of the elaborate “One China” understandings that have underpinned US-China relations since they were established 40 years ago. To abandon it now in favour of an unambiguous commitment to defend Taiwan would quite probably be seen in Beijing as a decisive US step towards abandoning “One China” and recognising Taiwan as an independent country. That could easily provoke exactly the Chinese attack on Taiwan that US policy aims to deter.

This is no doubt why the Biden administration last year declared that strategic ambiguity would not be abandoned. Nonetheless, the problem of strengthening America’s deterrence of China remains, and with no prospect that America’s military position in East Asia will improve materially over the years to come, some kind of new declaratory position appears the only way to do that.

It seems we can now see the solution that the White House has chosen. They have split the difference by half-abandoning strategic ambiguity, and half-affirming it, with Biden saying one thing and his administration saying another. Their thinking is, presumably, that Biden’s unambiguous statements will make Beijing think twice before attacking Taiwan, while his officials’ solemn reaffirmation of strategic ambiguity will deny China any grounds for declaring that America’s One China policy is dead.

The big question, of course, is will this work? Much depends on how Beijing interprets the various messages they are now receiving from Washington. Rob Ayson’s recent article in The Interpreter has some excellent points to make on this, especially on the significance of specific wordings.

My hunch, however, is that nothing Washington is saying makes much difference to Beijing’s calculations about the risks of attacking Taiwan. The Biden administration’s ambiguous repudiation of strategic ambiguity will do little if anything to counterbalance the big, brutal fact – that as China has grown stronger, the cost to America of defending Taiwan has grown to far outweigh the imperatives for it to do so.

A war with China really would be World War Three. Biden has told the world that he is not willing to fight that war for Ukraine, so why would the Chinese believe that he will fight it for Taiwan? Until he can articulate an unambiguous answer to that question, the Chinese will continue to become harder and harder to deter. And the risk will grow that if or when the Chinese attack, Biden will find that he has talked himself and his country into a war they cannot win and do not need to fight.