This article is based on this month’s episode of the Little Red Podcast, Tiananmen’s Final Secret.

In the final moments of this week’s episode of ABC Four Corners recounting the pro-democracy movement in China that came to an abrupt halt 30 years ago, former student leader Wang Dan observes, “Today’s China comes from 1989”.

A new trove of documents, unearthed by publisher Bao Pu, adds credence to Wang Dan’s statement. While stories about Tiananmen tend to end with the killings in Beijing, and are overshadowed by the iconic “Tank Man” footage, the silent weeks afterwards were more crucial, as this is when the political course of present-day China was set.

Bao Pu’s collection, The Last Secret: The Final Documents From the June Fourth Crackdown, synthesizes what scholars already know from the memoirs of deposed General Secretary Zhao Ziyang and the diaries of hardline former Premier Li Peng, but also breaks the silence. The Last Secret reveals details of two extraordinary meetings of the expanded Politburo held from 19 to 21 June.

In those meetings, high-ranking officials came forward and ritualistically praised the efforts and words of Deng Xiaoping and Li Peng, and condemned the actions of Zhao Ziyang while expressing support for Deng’s economic reforms. In effect, it was a humiliating groveling session that would not have looked out of place in imperial times.

There were no efforts to gather facts about what had just happened, or any contrition about ordering the killing of their nation’s children. Social policies to address the grievances of students and workers weren’t put forward. Rather than obvious causes – rampant inflation and corruption – the Party elders blamed hostile foreign forces, from George Soros to the Voice of America.

There was however, a push to end the factionalism that had seen Deng purge two general secretaries in as many years. Many complained that Zhao, despite his liberal leanings, was not a collective leader. Song Ping complained:

He took advice only from his own familiar group of advisers. [We should not] lightly trust ill-considered advice to make wholesale use of Western theories put forward by people whose Marxist training is superficial, whose expertise is infirm, and who don’t have a deep understanding of China’s national conditions.

Names had driven the crackdown – the People’s Daily labelling the movement as “turmoil” (dongluan 动乱), with its Cultural Revolution undertones, set the government on a course for martial law and murder. Two weeks after the carnage in Beijing and Chengdu, a name arose from the meetings that set the course for present-day China. It was not a name that foreshadowed a more collective, consensus-driven approach to ruling China.

The concept of a strong “core” (hexin 核心) leader was put forward and endorsed by hardliners such as Bo Yibo – the father of Bo Xilai, Xi Jinping’s ill-fated rival – as a solution to factionalism and the shortcomings of collective leadership. Jiang Zemin awarded himself the mantle and managed to avoid being purged, but Deng continued to rule from behind the throne and without deep networks, Jiang was core in name only. My colleagues in rural Anhui had their own verdict – he looked like someone “playing the part of chairman”. Only Premier Li Peng had more jokes about him.

Jiang did, however, manage China’s first peaceful transfer of power to his successor, Hu Jintao. For many Beijingers sympathetic to the democracy movement, and for many Western scholars, the transition sparked hope that the Party was taming itself, becoming increasingly institutionalised, and that perhaps law as well as prosperity was part of the Party’s post-Tiananmen pact with the people. Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao (who had stood alongside Zhao Ziyang as he addressed students in Tiananmen Square), particularly in their first term, fostered this hope. They eschewed the core label, delegating tasks – and responsibility – to their underlings.

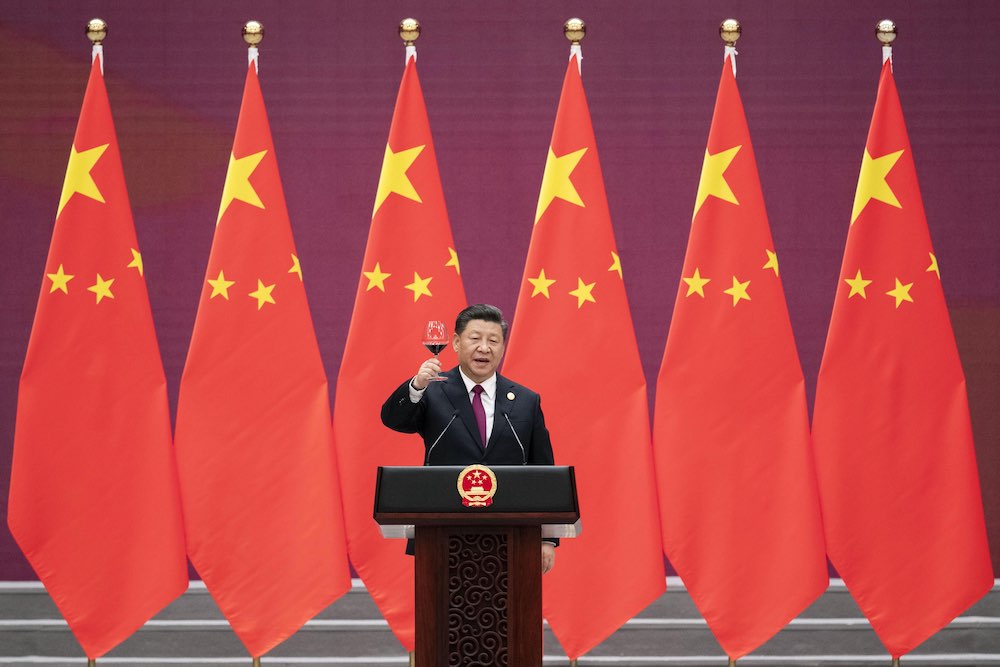

In 2016, nearly three decades after the killings, China finally had a chairman who was a core leader in name and in reality. Xi Jinping deployed the anti-corruption campaign to purge his rivals, and elevated loyalists to key posts. Now, with the removal of term limits, Xi’s power is now absolute and absolutely fragile.

As Ryan Manuel has cautioned:

the genius of the Chinese system is that call and response allows you to dodge accountability. Xi Jinping, frankly in some ways to his credit, put his face and his name on a whole bunch of reforms that if they go south, no one's seen that before. Deng Xiaoping ruled with his highest government position being head of the Chinese Contract Bridge association.

Three decades ago, China’s most senior leaders wished for a strong leader. With the Party purged of dissenters and those left about to be swept up in a campaign to “stay true to our founding mission” the Party elders finally have their wish. But life is lonely at the core. Xi can still blame hostile foreign forces if the China Dream fades, but he has no Zhao Ziyang to take the fall, or an obvious heir.

The old men who grovelled before Deng in 1989 should have been a bit more careful about what they wished for.