Australia and India are already working together to advance their clean energy ambitions, but not on the scale that the relationship finds itself in other spheres.

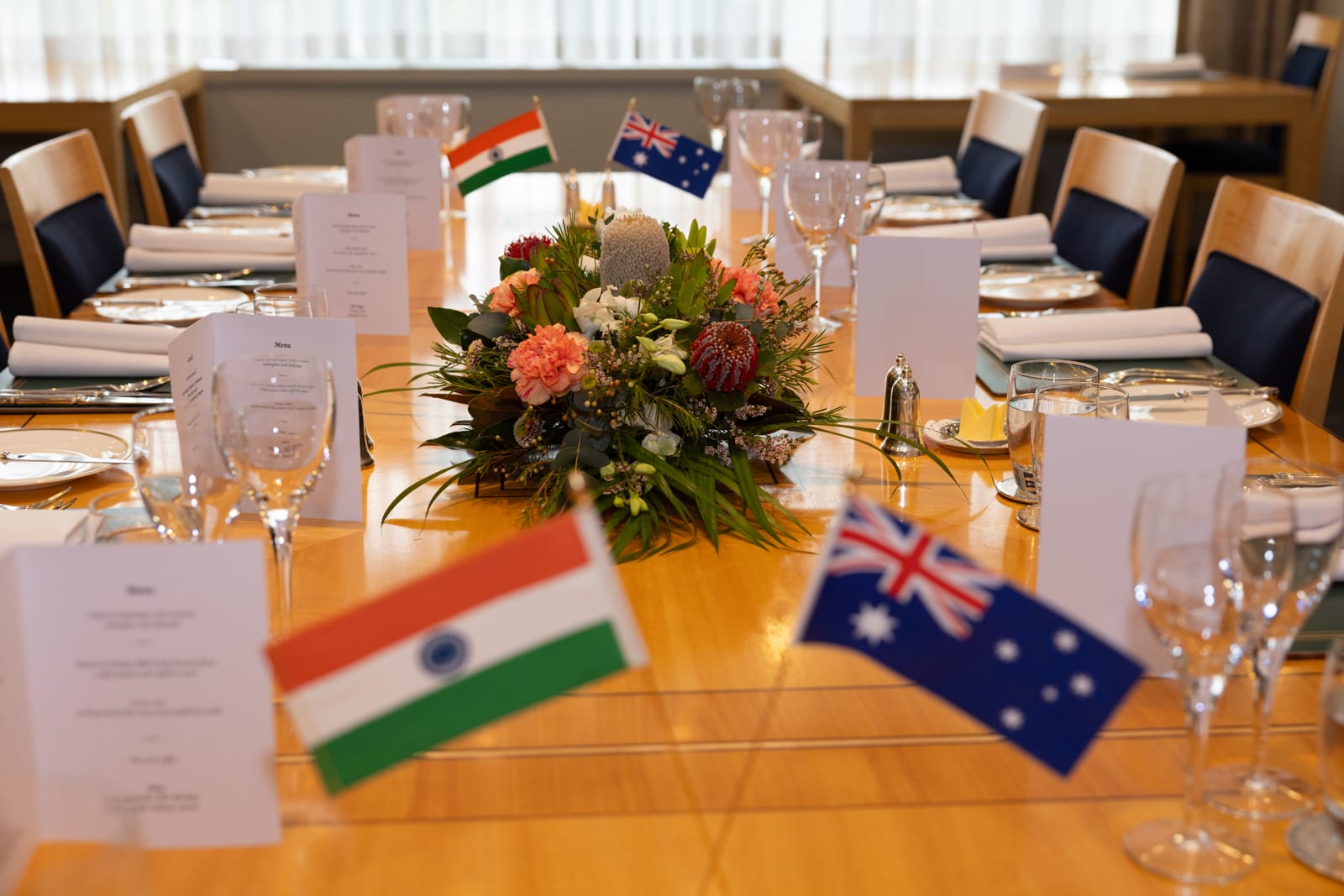

Serious efforts to kick start the renewables partnership began in early 2023, with two-way prime ministerial visits between Australia and India in quick succession. In New Delhi, prime ministers Anthony Albanese and Narendra Modi reiterated their commitment to implementing the Paris Agreement. They announced their intention to raise bilateral cooperation to the level of a “Renewable Energy Partnership”, and signed terms of reference for Australia-India taskforces on solar and green hydrogen.

The uncomfortable truth remains that coal makes up 85% of Australian exports to India.

Soon afterwards, India’s US$120 billion Reliance Industries, run by the country’s richest man, Mukesh Ambani, signed an agreement with Brookfield Asset Management to explore the manufacturing of renewable energy and decarbonisation equipment in Australia. This was significant because Indian industry scarcely commits to large investments in Australia-based renewables manufacturing. This deal will likely see the manufacturing or assembling of energy equipment, including solar photovoltaic (PV) modules, long-duration battery storage, and components for wind energy.

Despite this flurry of activity, efforts to advance the clean energy partnership appear to have gone cold.

The uncomfortable truth remains that coal makes up 85% of Australian exports to India. This sits at odds with the need to evolve Australia’s export basket beyond raw materials and conventional energy sources. Despite being the 9th richest economy per capita in Harvard University’s Economic Complexity Atlas, Australia ranks low as the 93rd most complex economy in the world. With iron ore, coal, and petroleum gases forming almost 51 per cent of its overall export basket, Australia’s economic complexity has worsened over the last few decades.

Meanwhile, India started its post-liberalisation era in the 1990s as the 60th most complex economy in the world, five places below Australia. Since then, its IT industry, which amounts to more than 30 per cent of its total exports, has grown exponentially, helping India outpace Australia, becoming the 42nd most complex economy in the most recent findings. The mismatch between Australia’s high income and low complexity means a precarious economic composition and growth prospects.

Renewable energy can diversify Australia’s exports with investments in advanced technologies and manufacturing of generation and storage equipment. The Reliance-Brookfield deal is a prime example of advanced processes and techniques developed offshore being applied in Australia.

Other Indian companies have also found Australia an attractive destination for renewable energy investment. Suzlon Energy grew to hold 30 per cent of Australia’s wind energy market during its peak phase of construction installing wind farms in Australia since 2004, and now averages at around 17 per cent.

On the flipside, Australia’s extractive industries can take advantage of advanced technologies developed in India. Beyond its mining operations, Technology Metals Australia aims to produce products such as vanadium electrolyte, a critical component of electric batteries. The company has been engaging with India’s Delectrik Systems to explore how to optimise vanadium production for the Indian energy storage sector.

Both countries have acknowledged there are barriers to entry. The Australia-India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement eliminated tariffs on more than 85 per cent of Australian goods exported to India, removing and reducing duties customs duties for critical minerals, and providing cheaper inputs for the Indian renewables industry. The enabling environment for investments in renewables in India has improved with Foreign Direct Investment of up to 100 per cent for renewable energy projects.

Australia’s technical expertise and extractive capabilities in critical minerals have also gained significance following the recent discovery of its lithium deposits. Australia produces 52 per cent of the world’s lithium, essential components of electric vehicles and storage systems. This will enable Indian firms to invest in Australian critical minerals that are crucial for battery manufacturing.

Sensibly, the two countries are bolstering their domestic policies to spur manufacturing capacity locally, and therefore attract more foreign investment. The National Reconstruction Fund and the Future Made in Australia policy provide a clear mission for Australia to strengthen its domestic manufacturing capacity. Meanwhile India has introduced the Production Linked Incentive scheme for high-efficiency solar PV modules.

Yet Australia-India collaboration in renewables remains bedevilled by a lack of understanding of the policies, capabilities and trade and investment opportunities on both sides. Many Indian firms see this as a roadblock to investment into Australia, while Australian companies struggle to navigate the Indian business landscape. The renewable regulatory frameworks, certification mechanisms and quality standards in the European Union and the United States appear clearer.

Nevertheless, the momentum is growing for Australia and India to collaborate on renewables. The inaugural Australia India Renewables Dialogue 2024 in Sydney this week, hosted by the Australia India Institute, will seek to jumpstart the renewables partnership by bringing together leaders in government, business, and academia from both countries to pursue partnerships in innovation, manufacturing, trade and investment. Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen will showcase Australia’s offerings matched by the Indian government doing the same. The challenge will be to ensure this new momentum in a shared commitment to decarbonise both economies doesn’t peter out, and the gaps in understanding and confidence between both countries’ renewables sectors can be bridged to forge a new joint clean energy future.