US President Donald Trump's decision to fire FBI Director James Comey has left commentators grasping for Watergate analogies. The 'Saturday Night Massacre' of October 1973 has been the most frequently cited, since this was the moment when President Richard Nixon fired Archibald Cox, the Watergate special prosecutor. Nixon's goal was to end the Watergate investigation. He failed spectacularly. Within weeks Nixon had to accept a new special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, who carried on the Watergate investigation in a quiet but tenacious manner. Within months, Nixon faced impeachment charges, which forced his resignation in August 1974.

Of course, the two moments are very different. Trump precipitated the current crisis by sacking the FBI director, not an independent prosecutor. And, although the intensity of the backlash has forced the Justice Department to appoint Robert S Mueller to investigate Trump's unfolding scandal, Mueller's position is somewhat different to that held by Cox or Jaworski. Mueller is a 'special counsel' who will remain nominally under the control of the Justice Department, can conduct business in secret, and only has to provide the Attorney-General with a 'confidential report' at the end of the process.

Even so, by taking on the FBI, Trump looks like repeating Nixon's Watergate actions in ways that should truly alarm him – and hearten his opponents.

The Watergate scandal began in June 1972, when five men were arrested for breaking into the Democratic Party's headquarters with bugging equipment. But, in many respects, the most important development had happened a month earlier, with the death of FBI Director J Edgar Hoover, who had run the organisation for almost fifty years. Hoover's death was crucial, because he had long wielded absolute power within the Bureau. Had Hoover lived a little longer, Nixon would almost certainly have leaned on him to limit the Watergate investigation. Hoover would have doubtless extracted a steep price for his cooperation, but there is a real possibility that the FBI's notorious autocrat would have strangled the investigation at birth.

As it was, Nixon had to pick a new interim director. Just as Trump's preference is clearly for a loyalist, so Nixon was also tempted by the prospect of having a friend at the head such an important bureau. The man Nixon chose was Pat Gray, who he had known since 1947 and who had a reputation for following orders. From Nixon's perspective, it proved a disastrous mistake.

Unlike Hoover, Gray lacked the clout to end the Watergate investigation. Even when Nixon instructed the CIA to approach Gray, asking him to call off the probe on the false basis that it would reveal sensitive CIA operations, Gray was unable to comply. 'The FBI is not under control,' Nixon's senior aide complained, 'because Gray doesn't exactly know how to control them, and their investigation is now leading into some productive areas.'

Just as bad from Nixon's perspective, many FBI veterans viewed Gray with deep suspicion. The most important of these seasoned hands was Mark Felt, who had been Hoover's number two. Felt was angry at being passed over for the top job. He was also alarmed by the prospect that Nixon might use Gray to politicise the bureau. So he responded in a way many officials do when backed into a corner: he leaked to the press. In Felt's case, this meant midnight meetings in underground car parks with Bob Woodward of the Washington Post. More than thirty years later, Felt would finally be revealed as Woodward's legendary source, 'Deep Throat'.

With the number-two man in the FBI providing a clear, if secret, steer, the Washington Post was emboldened to keep the Watergate story on its front page. That was one repercussion of Nixon's decision to appoint a loyalist. Another was Gray's disastrous confirmation hearings in March 1973.

As Trump will soon discover, presidents can't fire and hire FBI directors at will. It is one of the many jobs that require the advice and consent of the Senate. Gray became an overnight star at his hearings, but not in a manner that helped Nixon's cause. Gray's most damning revelation was that he had provided the White House with the FBI's raw Watergate files, an admission that immediately placed a major question mark over the integrity of the FBI investigation.

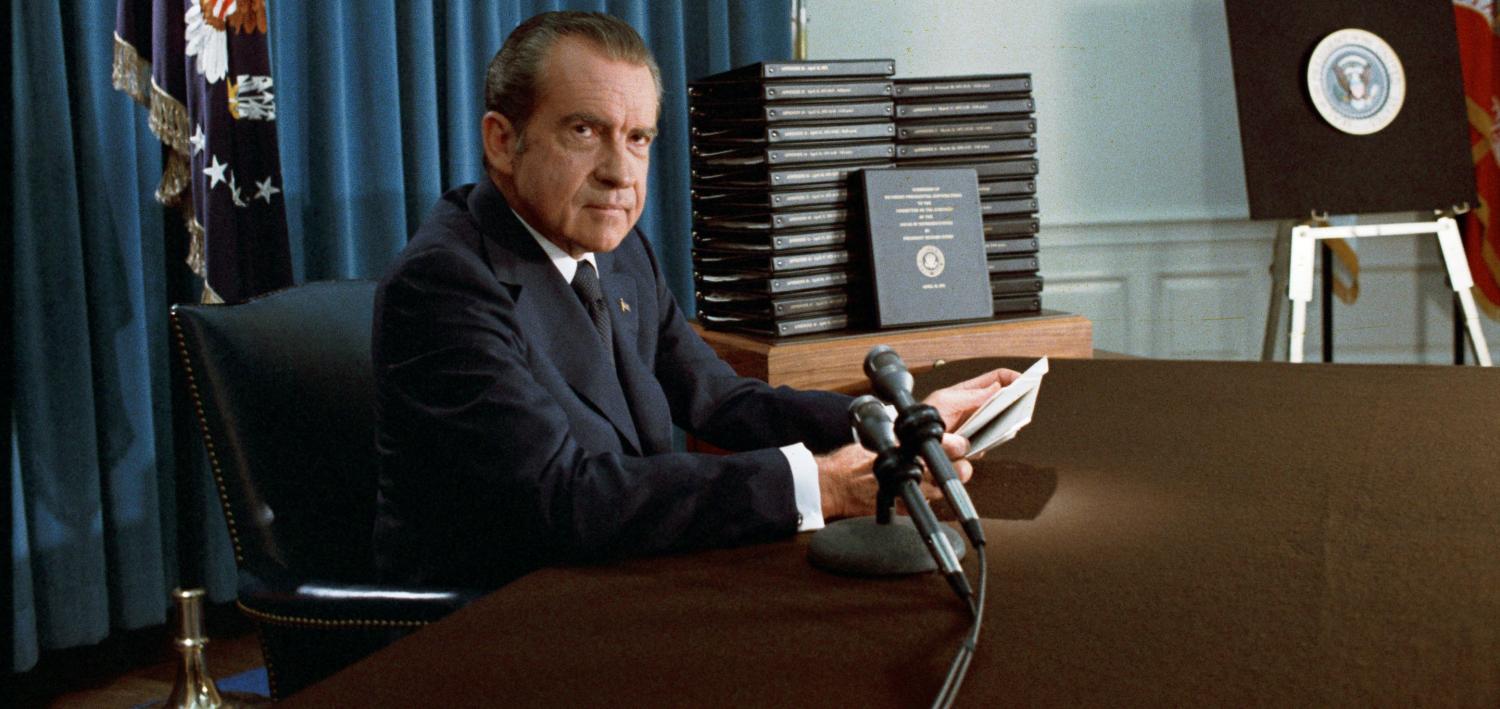

In the wake of Gray's failed confirmation hearings, the Watergate cover-up swiftly began to unravel. By May 1973, Nixon had no choice to appoint an independent special prosecutor to oversee the investigation. When Nixon's new attorney-general, Elliot Richardson, faced the Senate, he pledged that this prosecutor would have complete independence from political interference.

Thus Nixon ultimately ended up with the worst of all worlds: a truly independent prosecutor, who would be very difficult to fire. Which was exactly his problem six months later, on the Saturday night in October 1973 when he decided to get rid of Archibald Cox. This decision only became a 'massacre' when Richardson resigned rather than do Nixon's bidding, as did the number two man in the Justice Department. Losing three officials in one evening proved to be the tipping point for Nixon's presidency.

Nixon loathed Cox, a flamboyant figure he considered a bit of a showboater. In the firestorm following Cox's dismissal, Nixon had no choice but to accept Leon Jaworski, who went about his business in a quiet, steady, and, for Nixon's presidency, lethal manner. The culmination came in the summer of 1974, when Jaworski won the Supreme Court case, forcing Nixon to hand over tape recordings that exposed his direct involvement in a criminal conspiracy to cover up the Watergate burglary.

Just over a week after Comey's firing, Trump has ended up in a very similar position. Trump clearly hoped Comey's ouster would bring the Russia investigation to a grinding halt. Instead, he now faces a much more damaging probe from Robert Mueller, himself a former head of the FBI, who has a history of tenaciously pursuing cases wherever they lead.

As with Nixon, Trump's problems with the FBI are here to stay, and they might well prove equally fatal to his presidency.