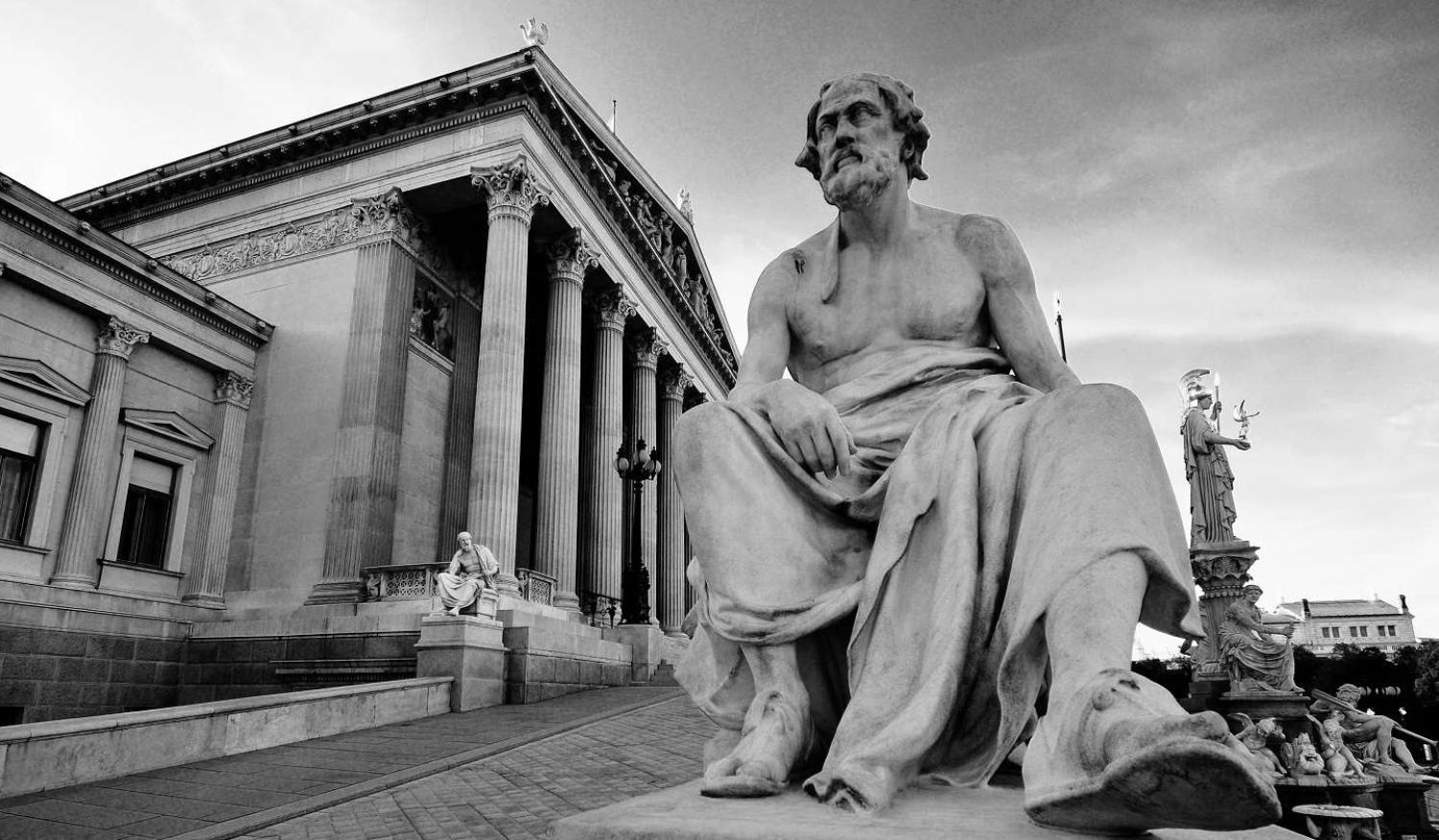

Thucydides is considered the father of a “realist” approach to the theory and practise of international relations. One of his more celebrated observations was that “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must”. More than two thousand years later, residents of Ukraine may be forgiven for thinking he knew something about the way the world works.

Yet the unexpected re-emergence of a very old-fashioned form of warfare in Europe has taken many observers and practitioners of international relations by surprise. Realists, by contrast, may be feeling rather smug as their claims about the inescapable nature of conflict and the human capacity for barbarism and brutality are once again vividly displayed. But if the cynicism and scepticism of realists is justified, what does this tell us about the prospects for peace and even progress in human affairs?

This is an especially consequential question for the population of Western Europe whose leaders thought they had left such horrors behind. Indeed, the unprecedented achievement of the European Union in pacifying and stabilising one of the most violent parts of the planet in the aftermath of the Second World War looks all the more remarkable in retrospect. The question in this context is: was the European peace an unsustainable aberration that was always hostage to history?

The all-too-familiar history of Europe makes this a potential turning point of the first order.

Even at the best of times, there were many who questioned the capacity of Europe’s distinctive institutional architecture to underpin endless economic development and what has been described as “the capitalist peace”. Greater economic integration not only turns out to have potentially unsustainable environmental consequences, but it makes even the most powerful economies vulnerable to the geopolitical pathologies of their trading partners.

Germany’s relationship with Russia is the quintessential example of this possibility. Many ageing Cold War warriors have highlighted what they see as the folly of Angela Merkel’s faith in the civilising influence of cross-border commerce. By contrast, German policymakers are now being praised for their supposed awakening to strategic reality and a concomitant willingness to spend more on defence.

The all-too-familiar history of Europe makes this a potential turning point of the first order. No country caused – or experienced – more suffering than Germany during the twentieth century. As in Japan, important lessons seemed to have been learned in Germany about the epic folly of war and the dangers of blindly following unconstrained leaders; something that ultimately resulted in a welcome repudiation of militarism in both countries.

Now we appear to be witnessing a profoundly depressing return to geopolitical business as usual as the world’s diminishing band of liberal democracies responds to what Australia’s prime minister has taken to calling the challenge presented by an “arc of autocracy”. All too predictably, the first instinct in Australia is to ensure we are in “lockstep” with our principal allies and invest in yet more military hardware.

The intention here is not to offer a critique of the futility and ineffectiveness of “deterrence” policies – although we are currently being provided with yet another painful reminder that ultimately they do not work – but to ask whether this is really the best Australia can do, and what that might mean for the way it conducts domestic and international politics if it is.

It is important to remember that when seen in the long sweep of history, the conflict in Ukraine – appalling, brutal and dispiriting though it may be – is not even the world’s greatest problem. The continuing disintegration of the natural environment on which we all ultimately depend remains the defining collective action dilemma of our times, which if left unresolved will undoubtedly make conflict more likely everywhere.

The great hope, perhaps, is that there are sufficiently large numbers of people in the world who recognise that their fate is inescapably bound up with that of their counterparts elsewhere.

It’s important to remember that conflict remained endemic in large parts of the Middle East and Africa while Europe was manufacturing its moment of peace, progress and prosperity. Indeed, Putin’s forces perfected the art of obliterating cities and their civilian populations in Syria and Chechnya while Europe bought Russian energy and laid out the welcome mat for the odious oligarchs who profited from its sale.

The scales may, indeed, have fallen from our collective eyes regarding the fragility of international order, the contradictions of globalisation, the persistence of cold-blooded brutality, and the dangers of unaccountable, despotic leaders, but it’s still no clearer what is to be done. The rather sobering and deflating reality is probably not much; or nothing that the acquisition of yet more ruinously expensive, unproven military hardware can definitively fix, at least.

The great hope, perhaps, is that there are sufficiently large numbers of people in the world who recognise that their fate is inescapably bound up with that of their counterparts elsewhere. The generous response to Ukrainian refugees is a hopeful sign, albeit one that seems limited to fellow Europeans.

Unfortunately, our collective ability to ignore the plight of the oppressed and the persecuted in other parts of the world suggests that large scale identification with, much less effective cooperation on behalf of, the weak may be beyond us. Suffering looks likely to remain a defining experience for much of humanity, and not one that will be easily incorporated into the political discourses of the world’s besieged democracies and their claim to moral and governmental superiority.