South Korean President Moon Jae-in and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un are scheduled to meet for the first time on 27 April at Panmunjom, the “truce” village on the border of the two countries.

The rapidly changing security environment on the Korean Peninsula has reached a critical juncture. The South Korean foreign policy community’s attention is focused squarely on the first inter-Korean talks’ prospects of success, and the proposed (yet to be finalised) summit between North Korea and the US in May.

While not geographically close to the peninsula, Australia has a stake in the upcoming dialogues. In October, North Korea claimed Australia was “showing dangerous moves of zealously joining the frenzied political and military provocations of the US against the DPRK”, and would be unable to avert disaster if it continued supporting the US.

For Australia, the issue of North Korea is important as a microcosm of tensions between the US and China. This is something of a litmus test for understanding US commitment to the Asia-Pacific region, and its capacity to shape outcomes. But it is also revealing of the strategic manoeuvring between the two great powers that Australia depends upon and must continue to negotiate.

China’s own influence on Pyongyang is clear: because 90% of North Korea’s trade is with China, economic sanctions do not work unless Beijing is on board. The phrase “maximum pressure” is used by policymakers to denote the most intensive and wide-ranging mix of economic sanctions, military pressure, and public rhetoric that the international community can collectively employ to stem North Korea’s nuclear ambitions. While the US has managed to convince China to apply some sanctions, China has been reluctant to apply “maximum pressure” and recently hosted Kim Jong-un – in a sign it is also involved in the dialogues, albeit indirectly.

The dialogue goals

South Korea will will take four policy agendas to the talks.

The first goal is denuclearisation. South Korea hopes North Korea will halt its nuclear program as a short-term step in the much longer-term goal of achieving Complete, Verifiable and Irreversible Dismantlement (CIVD). This goal is shared by Australia.

The second goal is permanent peace on the peninsula. The Moon administration is opposed to a military solution and has sought to reassure North Korea that it does not seek the collapse of Kim’s regime.

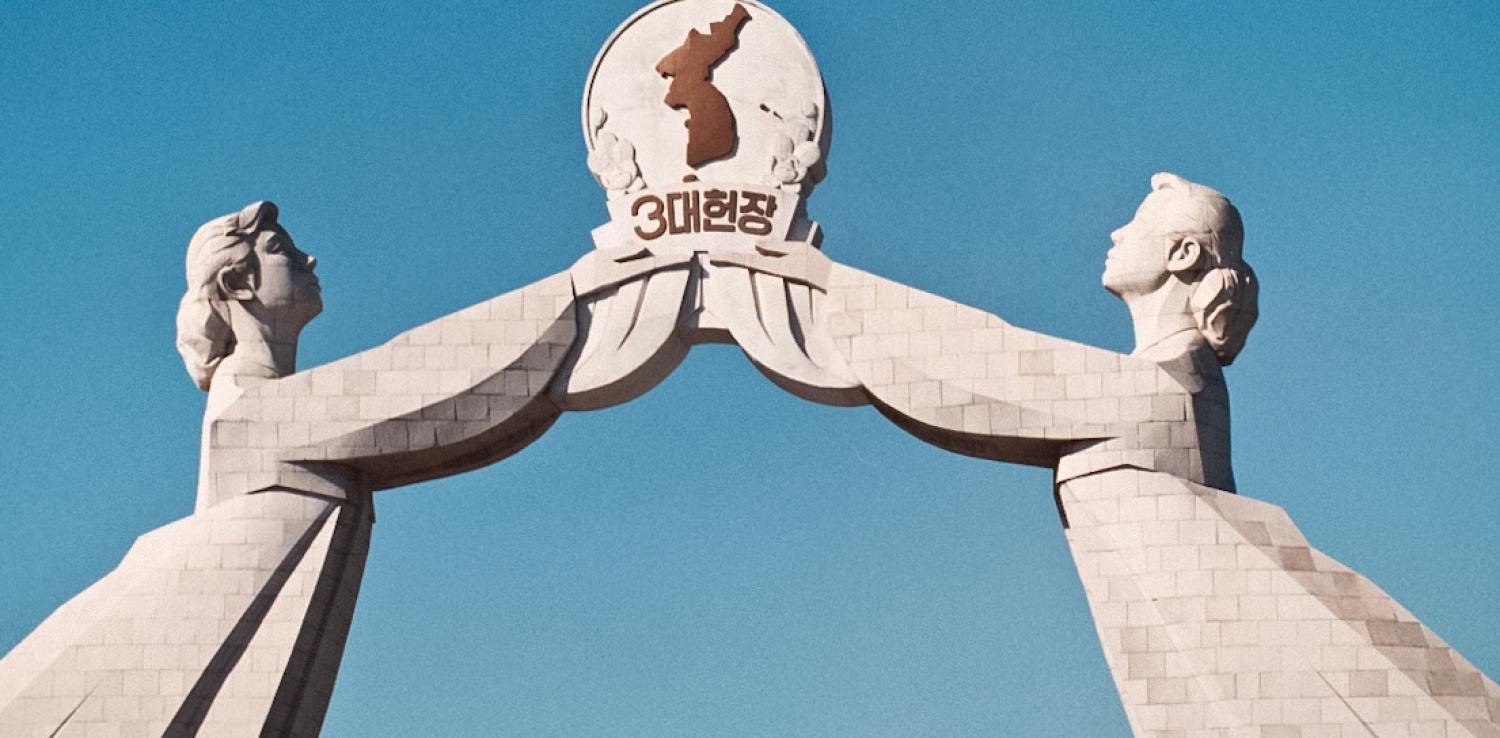

The third goal is re-establishment of “normal” relations between North and South Korea. However, the ultimate objective is unification. Reconciling some of South Korea goals – for example, its commitment to the continuity of Kim’s regime and to the long-term goal of unification – is not possible.

Still, the Moon administration’s “progressive” approach sees the dialogue as part of a long-term reduction of tensions via confidence-building measures, exchange and cooperation between North and South Korea, and humanitarian assistance and aid given from South to North.

The reduction in tensions while the summits are being coordinated is also viewed as a beneficial outcome of pursuing dialogue.

In contrast, “conservatives” are concerned about what South Korea or the US might compromise in order to strike a deal with the North Koreans. They want “maximum pressure” to be maintained. They are also sceptical about US President Donald Trump’s capacities to negotiate a deal with North Korea that would not sacrifice South Korea’s security interests.

Like the Moon administration, Australia’s interests should be in peaceful solutions, such as dialogue and sanctions, rather than military solutions. It seems unlikely that Australians would countenance becoming involved (again) in a faraway conflict due to ANZUS treaty commitments.

Yet Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has already said that Australia will follow the US if there is a war with North Korea.

Australia also has an economic interest in a peaceful Korean Peninsula. While often overlooked in Australian foreign policy commentary, South Korea is Australia’s fourth largest trading partner.

Watchers from afar

For peripheral states such as Australia, the capacity to substantively contribute is low. Australia also has a role to play in applying “maximum pressure” on North Korea. It has a role to play as part of the broader international community committed to denuclearisation, human rights, and peace-building on the peninsula, which requires a regional and global approach.

Australia publically supports any dialogue that might contribute to peaceful denuclearisation and North Korea’s adherence to UN security resolutions. However, foreign ministry statements have also noted that North Korea has a history of making agreements in dialogues, and then failing to honour them.

Yet, on this issue, Australia has little option but to defer to its security partner, the US. Australia has put its trust in Donald Trump and his transactional, “deal-making” style of diplomacy, yet his unpredictable, reactive approach to international relations increases the precarious and uncertain security environment in the East Asian region.