The 2020 US presidential election may well go down in history as the “China election”. Indeed, if the past month has been any indication, the narratives around this race for the White House will heavily feature how each candidate plans to manage the rapidly deteriorating relationship between the world’s two biggest economies.

Trump and his campaign have aggressively attempted to promote him as the “tough on China” President, even going as far as to label his putative rival with the moniker “Beijing Biden” in a recent attack ad. Yet team around former vice president Joe Biden seems comfortable using China as the playing field for political mudslinging, responding with an ad accusing Trump of being too trusting of Xi Jinping, and failing to adequately protect the American people from the Covid-19 outbreak.

But as each side of politics attempts to position itself as the one most able and willing to take on China, it is not yet entirely clear who Beijing views as its preferred candidate.

It seems safe to assume that any alternative to a presidency as globally unpopular as Trump’s will improve America’s standing in the world.

Precedent offers little indication. While traditionally hesitant to outspokenly support one party or another, China’s leaders have historically seemed to display a degree of greater ease when dealing with Republicans. It was the Nixon administration which famously established formal diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China. Henry Kissinger and Hank Paulson, both former cabinet officials in Republican administrations, appear to have achieved degrees of trust and success with Beijing’s Party establishment that is extremely rare among America’s political elite. In the years of China’s reform and opening up, the pro-globalisation economic policies championed most loudly by the Reagan and post-Reagan Republican party were beneficial for corporate America and exporters alike.

Whether as a result of active decision-making or of sheer luck and circumstance, the fondness expressed in Beijing for certain prominent Republicans doesn’t seem to have a clear parallel among Democrats. Hillary Clinton, for example, has a track record with China’s rulers that could at best be described as “complicated”. Her reputation as an outspoken critic of human rights-violating regimes around the world understandably makes China’s Communist Party officials uncomfortable, and many Chinese associate her with a tendency for self-righteous preachiness of the United States that they perceive and resent.

It’s partly for these reasons that support for Trump in the 2016 election was a common sentiment in China. His deal-making attitude as a “businessman” led many to believe that he could be easier to negotiate with than more ideological American presidents of the past. Trump’s “America first” approach to foreign policy offered opportunities for China to expand its global influence as the US focused inward. And although perhaps driven less by interests-based strategy than simple human emotion, many simply would be happy for any instance which would knock the US’s global prestige down a few pegs.

China and the Trump presidency

Regardless of the degree to which Beijing may or may not have preferred Trump to Clinton, it appears fair to say that they, like much of the world, have found the decision-making of the current President difficult to predict. Despite Trump’s fiery campaign rhetoric towards China, Xi and his fellow top leaders do seem to have been taken by surprise by how aggressively the tough talk was followed through on. “Prior to 2016, Beijing’s assumption has been that there was a default template for politicians’ strategies during a campaign and after the campaign,” explains Rui Zhong, China analyst for the Wilson Center in Washington DC.

While on the trail, American politicians tended to stick to being tough on states (like China) that the US was competing with, and then moderate that position after getting into office.

Yet rather than moderate its position, the Trump administration has doubled down. In a cabinet that has seen record-setting amounts of staff turnover, fierce “China hawks” have consistently had the ear of the president. Mike Pence, Mike Pompeo, Robert Lighthizer, Peter Navarro, and Matthew Pottinger have played prominent roles the administration’s approach to China, one that has only intensified in its antagonism. Under Trump, US-China relations have reached their worst point in nearly half a century, as a trade war, tech tensions, and a series of nasty spats over global influence leave very little room for cooperation between the two superpowers.

Unlike previous Republican administrations, this presidency has done little to gain the support of the pro-China corporate elite, but instead courted the populist right far less interested in China’s massive market and far more concerned about the threat of Chinese economic and military power.

Is Biden Beijing’s candidate?

Considering Trump’s confrontation with China, it’s tempting to conclude that Beijing would welcome a Biden victory in November. Indeed, there are some indications that this is the case. The former Delaware senator has for decades supported the “China engagement” doctrine, including throwing his support behind the granting of Most Favored Nation trade status in 2001. Biden is a known commodity for Xi, having met with him on a number of occasions in his capacity as Vice President. What’s more, the pro-globalisation corporate lobby that has lost some influence in Trump’s Republican party may be finding more of a home – and more influence – as “Biden Democrats.”

Op-eds in China’s state-run media have also indicated that the relative predictability of a likely center-left Biden White House would be more comfortable for Beijing than the current state of affairs. Other Chinese commentators have somewhat-cynically theorised that the liberal idealism of the American left offers opportunities for exploitation by the PRC that the hawkishness of the right does not.

Yet although some in Beijing may feel more comfortable working with a hypothetical Biden-led America, there’s a strong case to be made that four more years of Trump is in their best interests. Any hopes of a “return to normal” post-Trump appear increasingly fanciful as the presidential race goes on. In his long career in Washington Biden has been known to change his positions, but one thing has remained consistent: he has always had a sharp sense of the current consensus in both Washington and the Democratic Party, and has rarely strayed far from it. Currently, that consensus is that China is not a friend to the United States.

As a bipartisan tide in Washington turns against China, the areas in which a Biden administration’s posture towards China could differ from Trump’s are limited. However, there are a number of areas where a shift away from Trump-style foreign policy could hurt Beijing. As a state with few formal allies but tremendous economic might, the withdrawal of the US from many of its global leadership roles under Trump has provided an opportunity for China to reorient its global diplomatic presence.

Barring unforeseen circumstances, it will be Xi Jinping who will be calling the shots from Beijing, and he will be doing so indefinitely.

In 2019, Malaysia’s then prime minister Mahathir Mohamed expressed this bluntly. “Well, it depends on how they behave,” he said when asked if his country would take sides in a US-China trade war. “Currently the US is very unpredictable as to the things they do.”

Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte has also distanced himself from the US and cozied up to China, to the point of tearing up a status of forces agreement, effectively ending the country’s longstanding alliance with the American military.

Even among close allies, the US has struggled to form a united front, as Germany, France, and the United Kingdom have all been very reluctant to ban Chinese telecoms equipment firm Huawei from providing their 5G network infrastructure.

It seems safe to assume that any alternative to a presidency as globally unpopular as Trump’s will improve America’s standing in the world. Yet while Trump attracts the lion’s share of the attention, there are many broader trends which transcend him. China’s power relative to the US has grown steadily over decades, and their interests are diverging in a number of ways. The era of US hegemony is coming to an end, and global power is becoming increasingly multipolar. This is unlikely to change, regardless of who is in the White House.

But … what matters, to the one person who matters most?

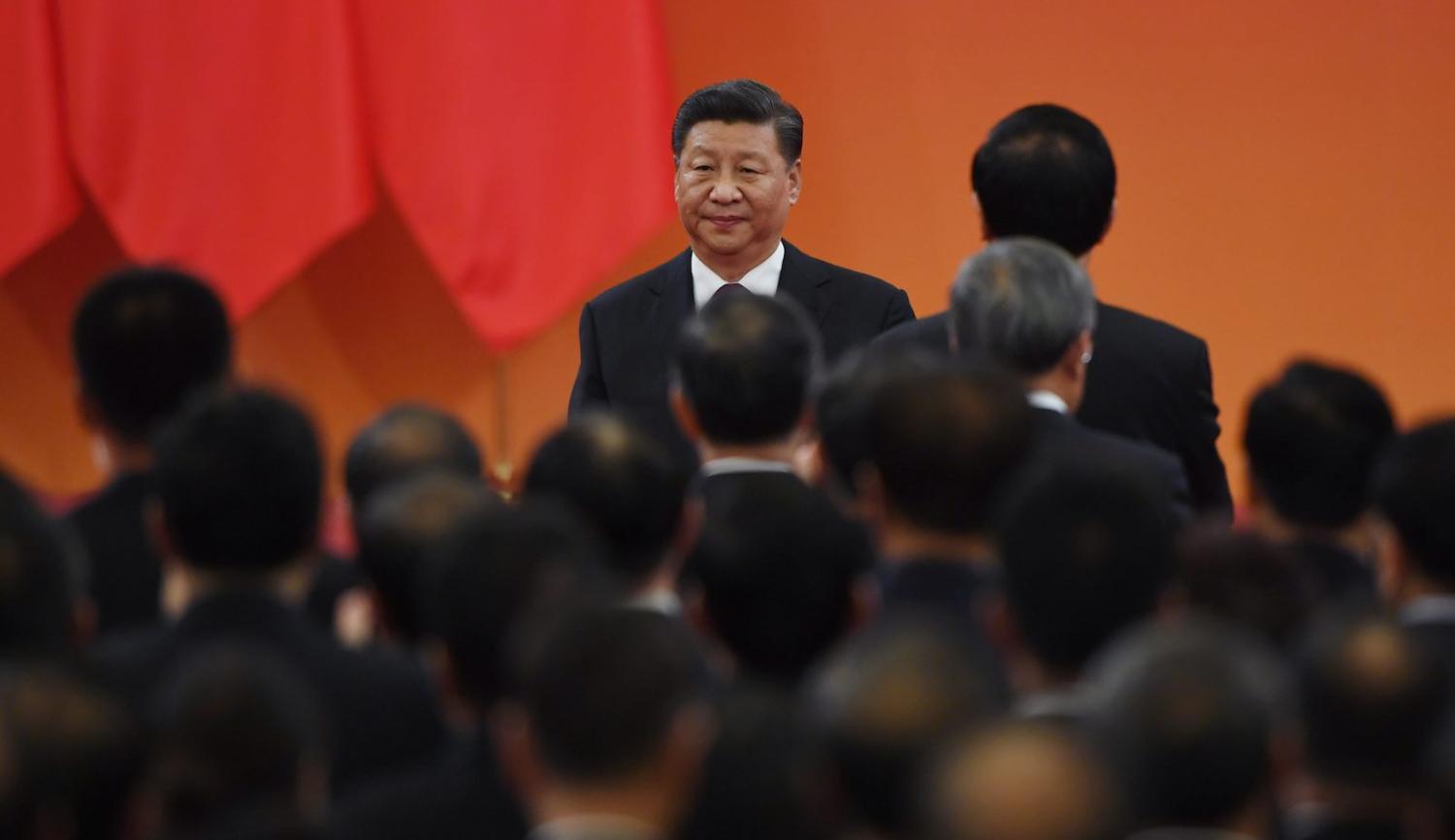

Yet as much as analysts may enjoy speculating how the two potential presidential scenarios could affect the geopolitical chess board, there is one constant that is highly unlikely to change: barring unforeseen circumstances, it will be Xi Jinping who will be calling the shots from Beijing, and he will be doing so indefinitely.

In his eight years so far in power his words and actions have displayed a consistent worldview. He is by nearly all accounts obsessed with maintaining internal control. He has ruthlessly and effectively consolidated power. Xi is a student of the fall of the Soviet Union, which he believes was largely a result of Gorbachev’s liberalising reforms. Whether in response to unrest in Xinjiang, protest movements in Hong Kong, online dissent, official corruption, or even a pandemic, Xi has used a number of tactics but has maintained one single strategy and direction: crack down, stifle, and take further control.

Xi appears quite willing to sacrifice international relations in the name of centralising his domestic authority. He has encouraged a nationalistic fervor both at home and abroad, embodied in a combative “wolf warrior” style of diplomacy that rallies China’s online mobs but severely harms their relationships with their most important trading partners. Considering his leadership priorities, this does make some sense. An open China, friendly and interconnected with the rest of the world leads to a population with many different interests, goals, philosophies, and yes, even leaders. A closed China that views the outside world as a threat has little choice but to rally around their leader.

There may be many people in China, its government, and the Communist Party that would rather deal with a Biden presidency, while others may prefer another four years of Trump. Yet at this moment, there only seems to be one person whose opinion really matters. And it appears his preference is perpetually whoever and whatever allows him to gain and maintain domestic control.