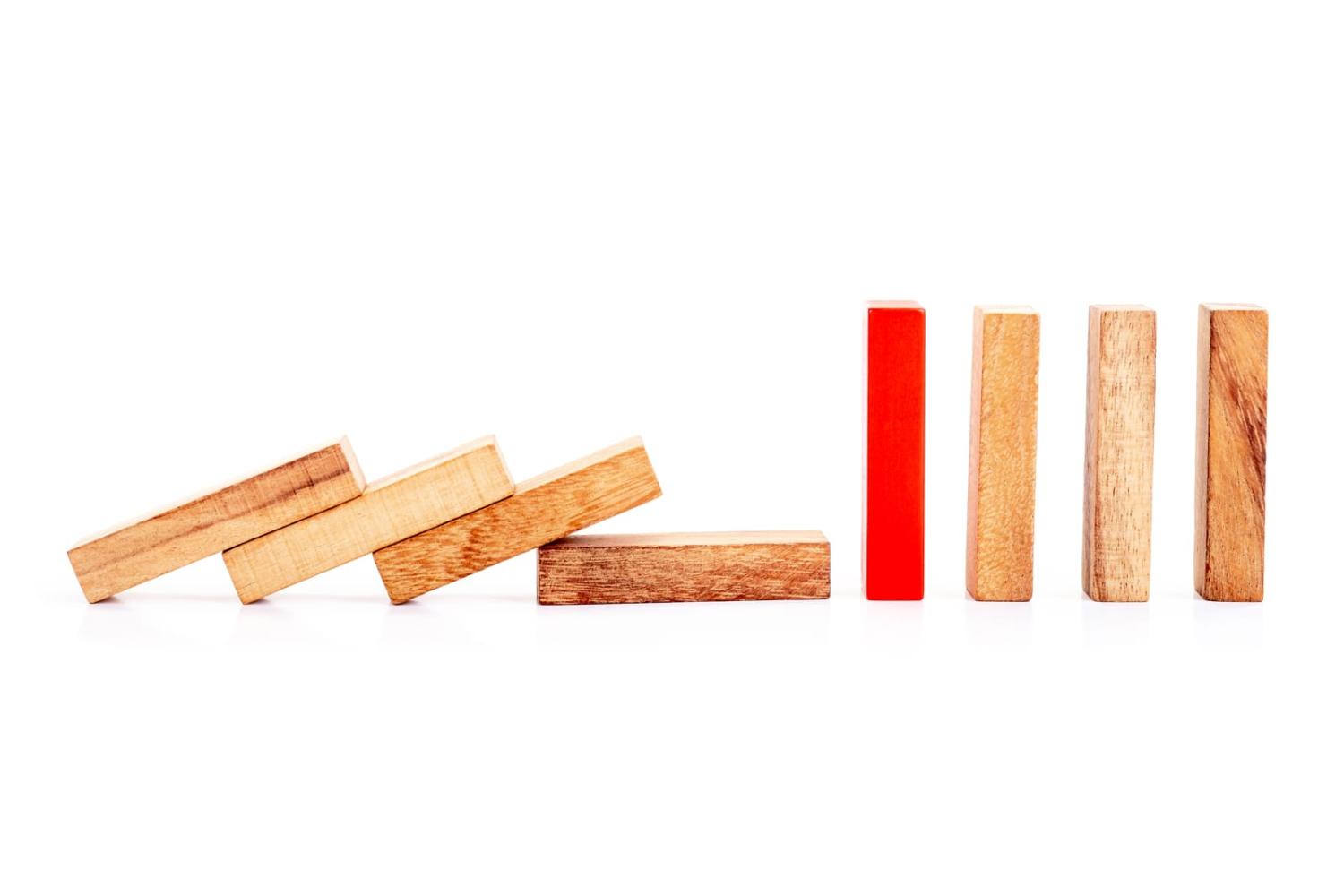

While “de-risking” has only recently entered the strategic vocabulary of Western policymakers, Japan has sought to de-risk its economy from China for well over ten years. Yet, the Japanese policy response to China’s coercive economic capacities has often been more ambivalent and less coherent than it initially appears.

Take the case of China-Japan economic integration. Following an escalation of tensions in 2010 between China and Japan surrounding the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea, China blocked the export of rare earths to Japan. In response, Tokyo began promoting the de-risking of supply chains for firms. This de-risking push has been partially successful, for instance for rare earths supply chains. In 2022, the government passed the Economic Security Promotion Act, which created the new position of the Minister of Economic Security, with the aim to develop more resilient supply chains while promoting infrastructure security and the use of critical technologies. Additionally, Japan has expanded fiscal support to firms to incentivise the reshoring and diversification of business operations from China, especially in strategically crucial industries such as semiconductors.

Despite this de-risking push, Japan has simultaneously promoted greater economic integration over the past years. Japan played a major part in advocating for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which will deepen economic integration with China. The RCEP was rejected by India and the United States for reasons including concerns about Chinese competition practices. Japan has also sought to promote a trilateral free trade agreement with Beijing and Seoul, although progress there has been limited.

Over the same time, the import of cheap, unsophisticated goods from China has declined, but Japan’s overall trade dependence on China has grown. This surging reliance is particularly pronounced in the import of advanced electronic goods, such as laptops.

Japan’s engagement with Chinese development financing has been similarly incoherent. Under then prime minster Abe Shinzō, Japan refused to join the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and Beijing’s Belt-and-Road Initiative (BRI), instead launching its own “Partnership for Quality Infrastructure” as an alternative to the Chinese initiatives. However, the Abe government and successive administrations then actively enabled and encouraged Japanese firms to become involved in BRI-linked projects in Southeast Asia.

This attempt to maximise economic gains with China while de-risking the economy reflects the gap in interests between the national security community in Japan and influential parts of the domestic business sector. In total, Japanese firms have become more pessimistic about their prospects in China. However, more than half of all firms operating in China still aim to maintain or increase their investments in the country. The present extent of China-Japan economic integration means that a push toward greater de-risking and decoupling would significantly hurt Japanese firms – including in key sectors such as electronic components and semiconductors.

Simply put, Tokyo’s national security objectives and the commercial aims of private sector actors are frequently disconnected. As business actors can inform the development and implementation of policy, Japan’s policy ends up being inconsistent.

This gap between government and business interests is not unique to Japan. Like Japan, South Korea has extended increased fiscal support for the reshoring of South Korean firms. However, big Korean multinationals have instead registered larger capital expenses in China and have preferred to diversify their operations to Southeast Asia, most notably to Vietnam. Firms have justified their decision with the embeddedness of their operations in China and the comparatively lower labour costs in Southeast Asia. When the interests of the government and the business community do not overlap, policy responses become less coherent.

To make its policy more strategically directed, policymakers in Tokyo and throughout Asia must ultimately incentivise greater cooperation from domestic businesses. This will also require enhanced cooperation with like-minded countries as global supply and value chains are being redrawn.