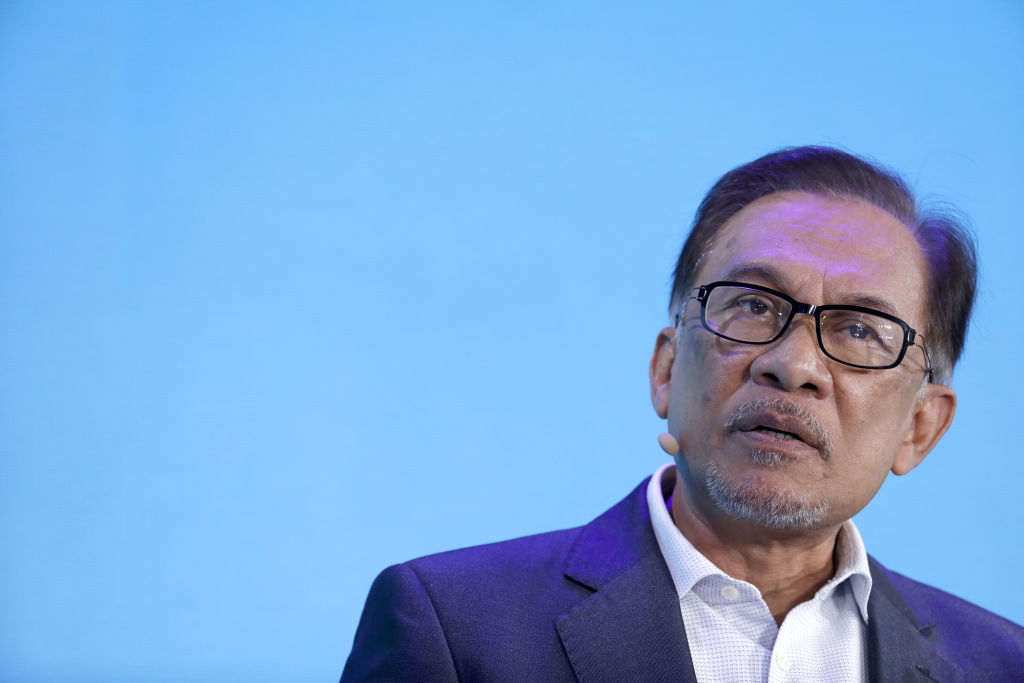

Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s latest promise that he “will not go more than three years” in the premiership is the latest in an ongoing saga of leadership succession within the Pakatan Harapan coalition government. While the coalition has insisted that there exists a “signed agreement” guaranteeing Anwar Ibrahim’s succession, observers have expressed doubts about the elder statesman’s willingness to cede power to his once estranged protégé.

These suspicions are not unfounded. While Mahathir and his Bersatu Party currently play an influential role within the ruling coalition, handing power to Anwar risks significantly diminishing the party’s influence. Such a development may prevent Mahathir from realising his vision for Malaysia –his raison d’etre for defecting to Pakatan Harapan in the first place.

The Prime Minister’s colourful personality and Pakatan Harapan chairmanship masks his rather precarious position within the coalition. Not only is the Malay Nationalist Bersatu a newcomer in a coalition of largely secular former opposition parties, it also controls only 26 parliamentary seats – significantly less than the Democratic Action Party’s (DAP) 42 seats and Parti Keadilan Rakyat’s (PKR) 50. Moves by Bersatu to recruit defectors from the opposition Barisan Nasional and establish a presence in Sabah were arguably attempts to strengthen its diminutive position in government.

Control of the premiership has allowed Bersatu to “punch above its weight” within the coalition. Aside from having greater latitude to direct the conduct of government, Mahathir has been able to retain control of key ministries for his party, with Bersatu controlling the powerful Home and Education Ministries. If Anwar takes over, power in the coalition would shift decisively to PKR due to his leadership of the largest party in the coalition, potentially engendering the loss of the advantages that Bersatu enjoys as the party of the Prime Minister.

Having been unfortunate in his successors, Mahathir is unlikely to risk his political vision in the hands of yet another “recalcitrant” heir.

In addition to these political considerations, it seems that Mahathir also intends to use his premiership to realise certain unfulfilled ambitions from his previous term. Having entered office with a commitment to seeing Malaysia become a developed country, Mahathir has revived his original Vision 2020 ambition, which he earmarks for completion by 2025. Pet projects such as a Third National Car have been re-introduced even as the Prime Minister has sought to settle old scores by reopening the Singapore-Malaysia Water Dispute last year.

It was perceived failures by Mahathir’s previous successors to adhere to his policy positions that led to the former Barisan Nasional stalwart defecting to the then opposition. He fell out with his original successor, Anwar, over disagreements over how to deal with the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. Subsequently, he intrigued against his next successor, Abdullah Badawi, over his refusal to build a “crooked bridge” to Singapore to reduce causeway congestion and was accused by Najib Razak of falling out with him over disagreements with his 1Malaysia Program.

Having been unfortunate in his successors, Mahathir is unlikely to risk his political vision in the hands of yet another “recalcitrant” heir – especially one who has crossed him before. This is especially since many of his policy ideas are no longer mainstream: once hailed as an act of economic nationalism, Mahathir’s obsession with developing a successful national car is now considered to be a poor use of taxpayer’s money. To realise his pet projects, the Prime Minister will have to retain the power and influence of his office.

Alternatively, Mahathir may wish to anoint a successor within his own family. It is speculated that Mahathir’s son Mukhriz – Chief Minister of Kedah and a rising star in Malaysian politics – has been earmarked for a long-term place of prominence in Malaysian politics. Not only would Mr Mukhriz be a more reliable vehicle for the achievement of the elder Mahathir’s political vision, his relative youth is also an advantage relative to the aging Anwar, who turns 72 in August.

It is questionable, however, if the other Pakatan Harapan component parties will be willing to accept a leader other than Anwar as head of the coalition. Having been energised and united under the banner Reformasi movement since 1998, the charismatic Anwar enjoys significant personal prestige within the coalition and serves as a rallying point no less powerful than Mahathir himself. While the coalition has agreed to accept Mahathir as interim leader to enlist Bersatu’s support to activate rural Malay voters, controversy about Barisan Nasional defections suggests that the component parties still harbour some distrust towards Bersatu colleagues.

It was for this reason, perhaps, that Mahathir was possibly cultivating Azmin Ali – the PKR Minister for Economic Affairs who is seen as close to the Prime Minister – as a sort of “compromise candidate” to succeed him. As a member of the largest party in the coalition and a Mahathir loyalist, Azmin’s leadership of the Pakatan Harapan could perhaps rally members behind Mahathir’s political programme. The recent implication of Azmin in a sodomy scandal, however, has called his political prospects into question.

When the then 92-year-old Mahathir put himself forth as the Pakatan Harapan’s presumptive prime minister, few would have imagined that he would be anything but a charismatic seat-warmer. Yet, the aging titan still holds sway in Malaysian politics and appears to be stalling for time to defend his pre-eminence. With a complex web of interests jostling for power within the ruling coalition, it remains to be seen if the Pakatan Harapan can stay united amidst the delicate process of leadership succession.