The stabbing attack last Thursday by an ISIS supporter on Wiranto, Indonesia’s top security minister, was a shock for several reasons. Attacks on senior officials in Indonesia are very rare, though terrorist attacks on police are common. Protection proved to be disturbingly lax – the stabber got right up to the door of Wiranto’s car. The weapon was a knife, not a bomb or a gun.

Most shocking of all, it turned out that the stabber, a man quickly identified as Syahrial Alamsyah alias Abu Rara, did not even know that his victim was Wiranto. All he knew was that a government VIP was coming to town, and he was determined to assassinate him as a representative of an idolatrous oppressor state. This is how ISIS supporters regard Indonesia, because it relies on democracy, with man-made as opposed to God-given laws.

President Joko Widodo’s call after the attack for the eradication of terrorism was naive. Marginal players such as Syahrial can be radicalised and inspired to undertake attacks for a variety of personal and ideological reasons.

Especially as the horrors of the Turkish invasion of northern Syria unfold and ISIS detainees under Kurdish control escape or are left to die in the desert, it is worth reflecting on Syahrial as an example of the impact ISIS – which is far from finished – has had around the world.

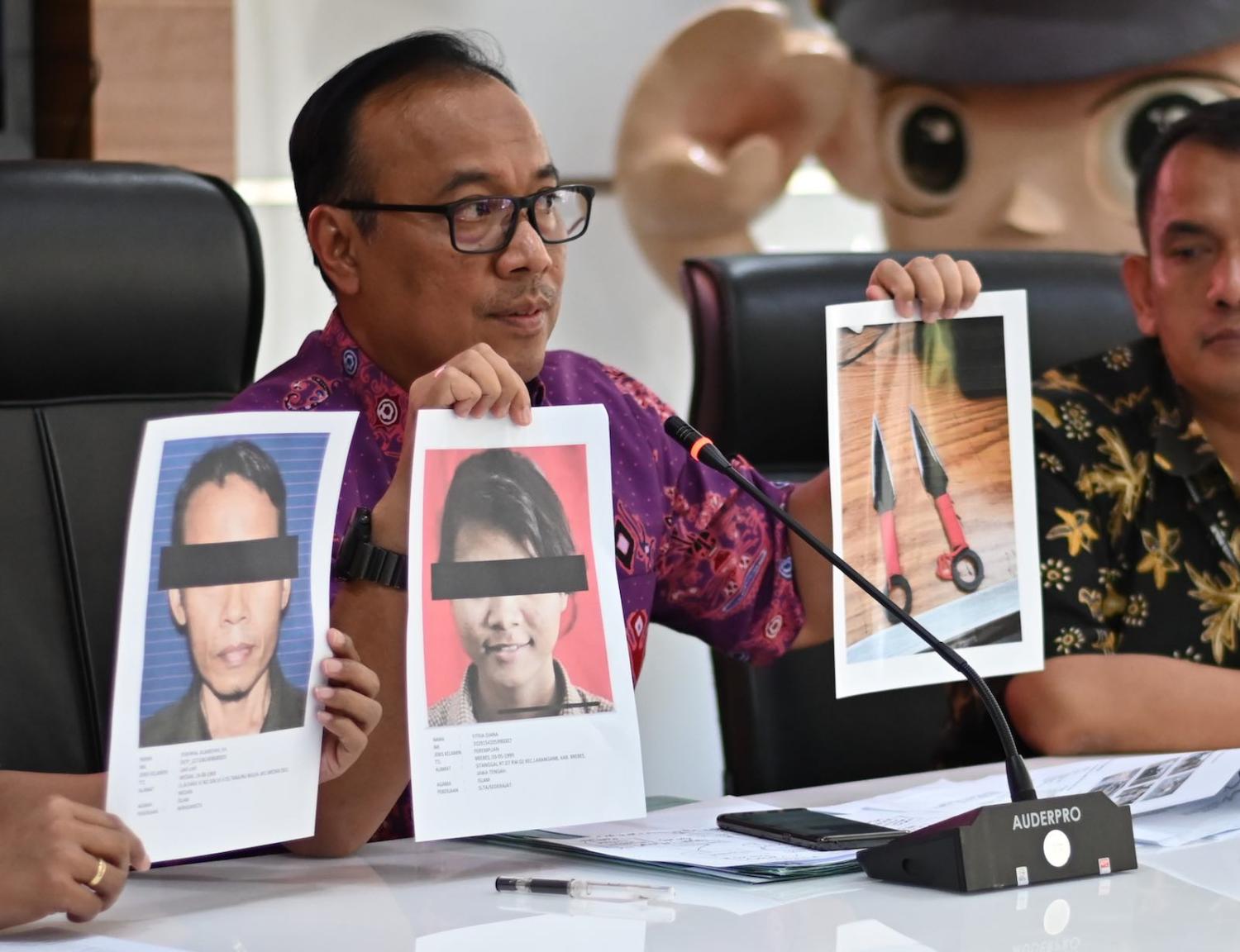

Syahrial appears to have been a totally peripheral player. Initial reports from the police suggested he was a member of Jamaah Ansharul Daulah (JAD), Indonesia’s largest pro-ISIS coalition, which, after repeated waves of arrests, has degenerated into a network of independent cells. He seems never to have been an active member, although it is important to remember that the police investigation is still in the early stages and there is much that has to be explored.

Syahrial had met Abu Zee, the amir of one such cell in Bekasi, a Jakarta suburb, in December 2018 through a pro-ISIS chat group on WhatsApp, Indonesia’s most widely used mobile phone application. They had a few friends in common, but according to Abu Zee (interviewed in prison by Indonesia’s news weekly Tempo, in an article in the 14–20 October edition), it was only in July when Syahrial asked him to perform a marriage ceremony for him and a new, much younger second wife last July that they met face to face for the first and last time. Syahrial never took part in Abu Zee’s religious study sessions or physical fitness training exercises, let alone indicated an interest in plotting violence. He did reportedly become very stressed after Abu Zee and other members of the cell were arrested last month on 23 September.

President Joko Widodo’s call after the attack for the eradication of terrorism was naive. Marginal players such as Syahrial can be radicalised and inspired to undertake attacks for a variety of personal and ideological reasons. This attack required almost no planning, training, or funds. His wife was his only collaborator, and he fully expected to die. This is what ISIS has left us with, and with events in the Middle East to serve as a constant goad, there is very little that deradicalisation or counter-radicalisation programs can do to make the problem go away.

Last month, on the anniversary of 9/11, a group of security professionals issued an open letter to Western governments warning of the deteriorating situation in the Syrian Democratic Forces-controlled camps for ISIS detainees in northern Syria and urging governments to repatriate their nationals, especially children. They wrote:

The squalor of the camps and the lack of just treatment there, especially for children, fuels the Salafi-jihadist narrative of grievance and revenge that has proven so potent in recruiting followers. Many of the women are victims of physical and emotional abuse, but some are also deeply radicalized, preaching toxic ISIS propaganda to the increasingly desperate detainees of al-Hol [the largest camp]. Detained children, growing up in brutal conditions and subjected to persistent indoctrination, are at particular risk of becoming radicalised and pursuing the path of terrorism. The denial of citizenship by their home nations will bolster their sense of being, in effect, citizens of the Islamic State, potentially preparing them to form the core of a future resurgence.

It is now too late to heed the warning. As Turkish troops move in to Rojava, thousands of ISIS detainees could become new martyrs to the ISIS cause. The danger is not so much that some will find their way back to this region. The bigger threat comes from the new life given to the ISIS narrative that people such as Syahrial, who never set foot in Syria, will use to justify violence.