Escalating geopolitical tensions between China and the West mean that Australia’s China debate is more important than ever. Discussions about key issues such as foreign interference, China’s economic statecraft, or military confrontation, however, can become much harder than necessary when concerns about discrimination and racism are not addressed.

For many, it is not an abstract construct. Across the West, increased anti-Chinese sentiment, particularly in the wake of the pandemic, has affected Chinese diasporas as well as others of East and Southeast Asian descent who were mistaken as Chinese or grouped as “Asian”. In Australia, the Lowy Institute’s Being Chinese in Australia survey found nearly one in five Chinese-Australians were attacked or threatened during the height of the pandemic in 2020. This continued beyond the pandemic, with a third saying they experienced discrimination in 2022.

Polling by the Australia-China Relations Institute from 2023 found 43 per cent of people believe Australians of Chinese origin can be mobilised by the Chinese government to undermine Australia’s interests and social cohesion.

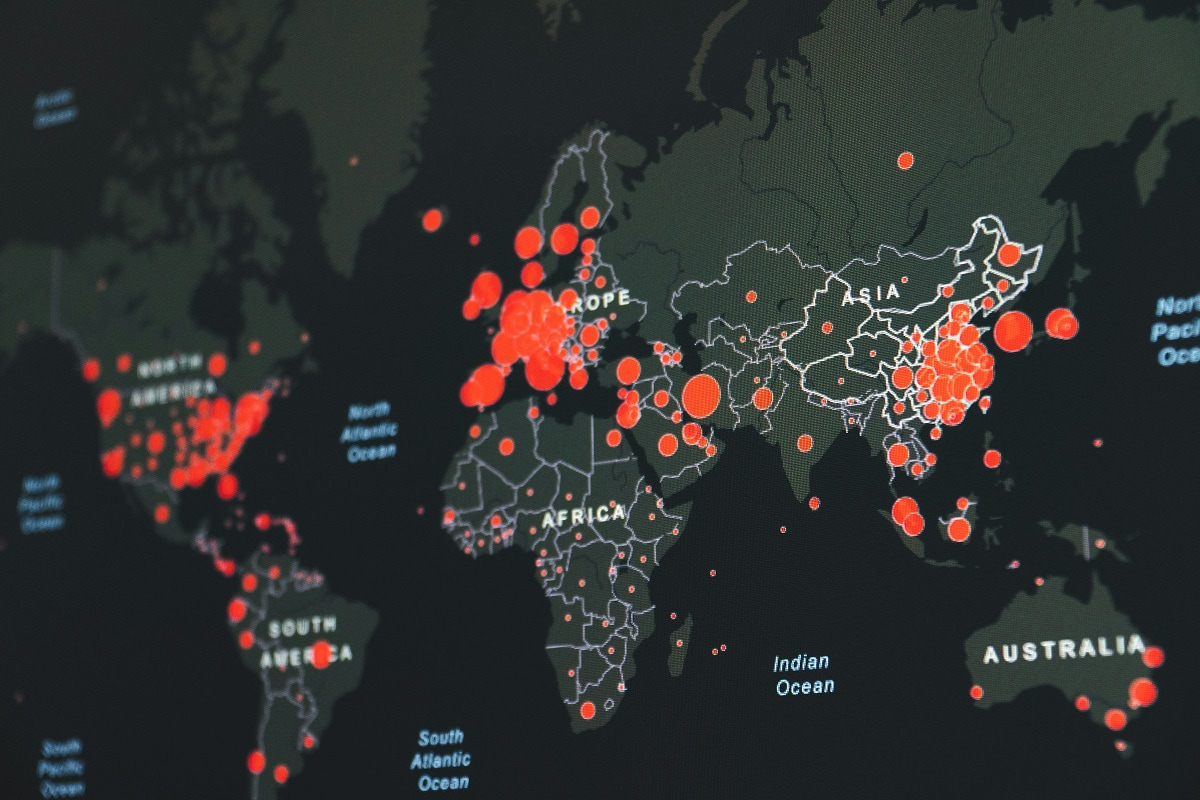

Experiences of racism were far from unique to Australia. While racism in the United States during the pandemic was well documented, similar waves in New Zealand, Canada, and the United Kingdom occurred. In this environment, there is concern about the role the China debate can play in fostering negative attitudes.

Studies have shown it is not a figment of people’s imagination. Polling by the Australia-China Relations Institute from 2023 found 43 per cent of people believe Australians of Chinese origin can be mobilised by the Chinese government to undermine Australia’s interests and social cohesion. A Melbourne University study found these discriminatory attitudes are influenced by economic conditions, political rhetoric and the media context.

This atmosphere can lead to fears about racism spilling over when there is a perceived negative focus on China’s behaviour. Claims of Sinophobia have been particularly polarising. The term, which can refer to both a fear of China but also broader anti-Chinese sentiment, has been used by the government of the People’s Republic of China in response to what it claims is the singling out or unfair treatment of China compared to other countries.

China sceptics dispute this, arguing criticism of the PRC or the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is attacked as Sinophobic to silence debate about human rights abuses, foreign interference and geopolitical manoeuvring. They argue racism has been weaponised as a wedge issue and must be pushed back against whenever raised.

While the use of specific slurs, inciting hatred, or violence against individuals of Chinese heritage are more easily identifiable as racist, navigating whether claims or actions are Sinophobic can be far more difficult and contentious. My own personal experience at a Senate hearing and debate over whether my treatment was even Sinophobic illustrates it is not only contested but there is no real guidance for those without a deeper grasp of anti-Chinese racism.

In response to concerns about anti-Chinese racism, the need to distinguish between Chinese people and the PRC government is regularly cited. Despite this, rhetoric can veer into what may be considered Sinophobic territory as the Chinese diaspora is seen as a vector of influence for the CCP. Examples include:

- Requiring Chinese people to act in a way not expected or demanded of any other group

- Denying, or minimising the significance of, discrimination against Chinese people

- Requiring Chinese people to criticise the CCP more vociferously than other people

- Accusing Chinese people of effectively being a “fifth column”

Identifying genuine Sinophobia is made more difficult by the unlikely alliances between some anti-CCP activists of Chinese heritage and the far right that emerged in the wake of the pandemic. Many of these activists reject any suggestions of Sinophobia and their views are used as proof that it is non-existent.

A working definition will not end racism, but it will improve the quality of the China debate.

There is no simple answer, but a working definition of Sinophobia may help to improve the China debate. Currently, no such definition exists despite a long history of anti-Chinese sentiment in many parts of the world. The purpose is to create an informed consensus about what may be considered Sinophobic. This is far from a radical idea. Many working definitions of forms of racism already exist, for example, for anti-Semitism, Islamophobia and anti-Roma racism.

Any working definition should be illustrative rather than a prescriptive list of features, providing examples of treatment that could be considered Sinophobic and background context that should be considered as guidelines. It must also be unequivocally clear that while rhetoric used can be Sinophobic, criticism of political institutions such as the PRC government and the CCP, or raising human rights concerns, is not.

A working definition will not end racism, but it will improve the quality of the China debate. Rather than silencing debate about Australia’s relationship with China, it will make it more difficult for bad faith actors, both domestic and international, to derail discussion by claiming or rejecting allegations of Sinophobia as individuals and institutions will have the tools to judge for themselves. By making it easier to focus on and tackle actual instances of Sinophobia, governments can better reassure Chinese diaspora communities that they are serious about addressing racism while openly discussing the range of challenges associated with China’s rise.