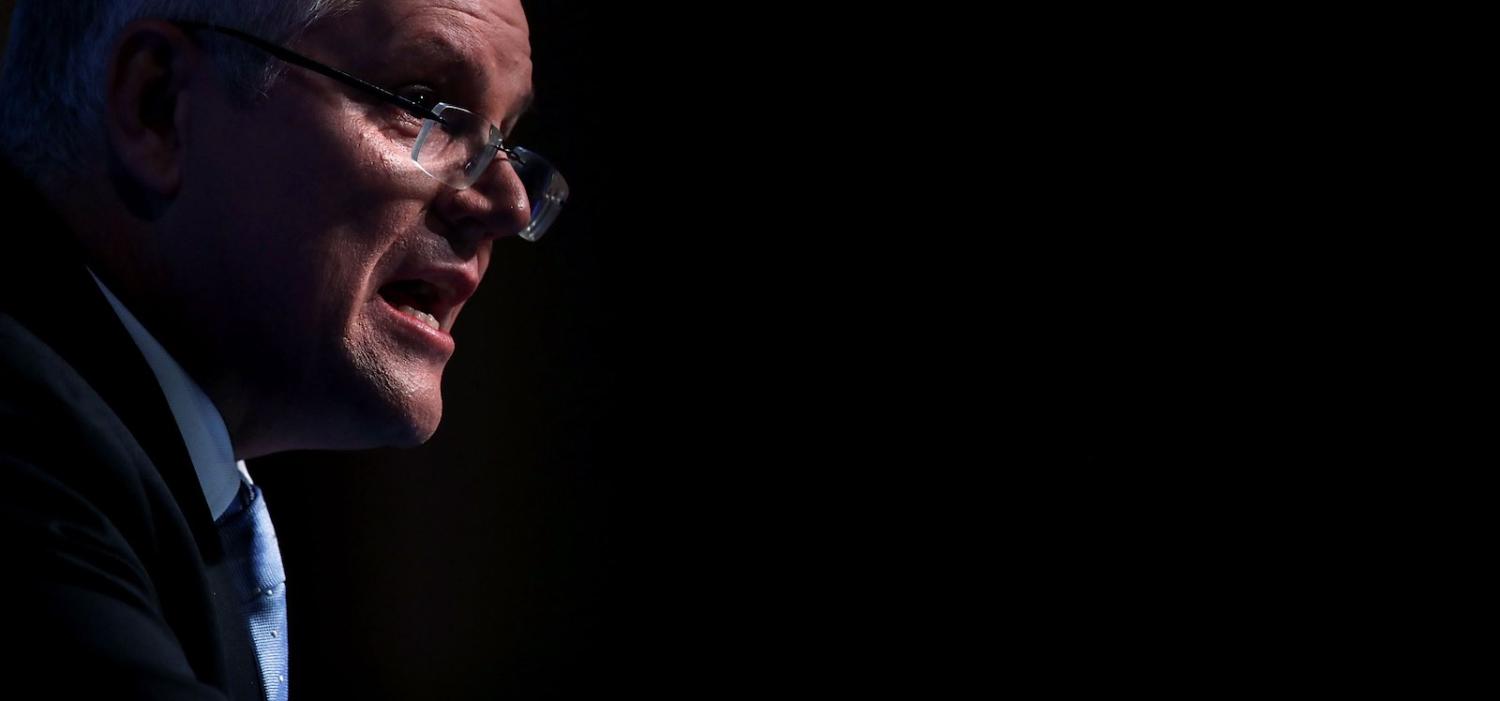

Healing bitter internal party divisions after a week of political bomb-throwing will be an onerous enough task for Scott Morrison, newly anointed Prime Minister of Australia. That’s before running the country, let alone positioning Australia in the world, or dealing with Donald Trump.

The politics are extraordinary. Morrison was once a darling of the conservative wing within the Liberal Party of the Coalition government, known in Australia and in the region, particularly Southeast Asia, as the architect of the uncompromising turn-back-the-boats policy on border protection. He rose from the immigration portfolio to be Social Services Minister and then Treasurer, widely considered the second most important job in government.

But Morrison had fallen from favour, with conservatives at least, for not doing more to prevent the toppling of another prime minister, Tony Abbott in 2015, when Malcolm Turnbull took control. Morrison was then criticised by some of these same conservatives for perceived lacklustre performance in charge of the national economy.

Enter Peter Dutton, the man who took over Morrison’s immigration portfolio, then oversaw the transformation of the security and intelligence apparatus in government with the creation a new super-ministry of Home Affairs. Dutton embraced the hard-man image and was urged by Abbott and other conservatives to challenge Turnbull, and give voice to the “base”.

Exit Dutton, when the move backfired spectacularly on Friday, after Turnbull stepped aside and Morrison was victorious in a ballot of party MPs, 45:40.

Morrison now has to bridge the divide, and as is the ritual following a leadership spill, pledges of loyalty have been made, including by Dutton. Abbott remarked wistfully following the ballot in the party room that saw Turnbull fall, “we’ve lost a PM but there is still a government to save”.

And many immediate challenges faced by the government are in the international realm.

Reports emerged on Friday about what had been Turnbull’s impending trip next week to Indonesia, including finally announcing a trade deal. As Lowy’s Aaron Connolly explained:

Sources in Jakarta tell me that @stephendziedzic's reporting is solid. The most difficult issues were resolved at the last negotiation in Melbourne. The agreement would not have been ready to sign in Jakarta, because these are technical documents and take time to prepare.

— Aaron Connelly (@ConnellyAL) August 24, 2018

Can Morrison afford to be away from Canberra and efforts to salve bitterness of recent days?

From Indonesia, the Australian prime minister was expected in Malaysia, the first meeting after the extraordinary political comeback of Mahathir Mohamad. Standing-up the man Paul Keating once branded “recalcitrant” might give Morrison pause.

And then comes the Pacific Island Forum. It’s worth noting that Morrison is well known to Nauru – host of this year’s summit – having regularly courted the country while in opposition to secure elements of what became known as Operation Sovereign Borders.

But that familiarity would not help Morrison navigate the very issue that bought this latest eruption of leadership instability in the Liberal party to a head: Australia’s policy on climate change. Morrison, who once dragged a lump of coal to the parliament to taunt his political opponents for wanting to impose greenhouse emissions controls, would face a tough crowd of island leaders confronting rising seas and more extreme weather should he show up on Nauru.

And in the middle of all the leadership ructions and upheaval, it was Morrison, acting as Home Affairs Minister, who announced the ban on Chinese firm Huawei from helping build Australia’s 5G – a move that on Friday the tabloid Global Times, in typically hysterical style, branded “hysterical”.

Assuming Morrison doesn’t bolt to an early election, in only a few months, he could also be host in Australia to Donald Trump (who Morrison chided for meeting with Vladimir Putin so enthusiastically, given the shooting down of MH17) as well as Japan’s Shinzo Abe, ahead of the APEC Summit in neighbouring Papua New Guinea.

When I delved into Dutton’s international outlook this week ahead of the ballot, it was clear he hadn’t said a lot about steering Australia in the world. Morrison has had more of a chance, but the details are still sketchy. As Treasurer, Morrison was involved in the G20 circuit. Combined with his background in immigration, where he dealt extensively with Sri Lanka and Cambodia, including a deal with Hun Sen’s government for resettling refugees, he will have some markers set out to guide his view. Nonetheless, with trouble at home and demands abroad, there will be no let-up in pressure.

Morrison put it this way, in a message as much to his colleagues as to the country, roiling after racist remarks and at times pointed debates on migration.

We have a lot of challenges as a country. And we will get through them as we always have. Together.

After a tumultuous week of attempted political coups, which saw New Zealand’s Winston Peters meet Foreign Minister Bishop in her last formal meeting in the job under Malcolm Turnbull, it seems safe for the Kiwis to send the troops home from Canberra. For now.

New Zealand flies in emergency administrator to Canberra with Winston Peters steering country back to democracy around 2022. President Jacinda Ardern says NZ can not risk failed state next door destabilising South Pacific pic.twitter.com/D4YaVPFORs

— Michael Field (@MichaelFieldNZ) August 23, 2018