Book Review: Xi Jinping: The Backlash by Richard McGregor (Penguin, Lowy Institute, 2019)

Book Review: Xi Jinping: The Backlash by Richard McGregor (Penguin, Lowy Institute, 2019)

Richard McGregor has written a dazzling account of the first six years of the Xi Jinping era and what he sees as the “backlash” to Xi’s increasing authoritarianism domestically and assertive foreign and defence policies.

This short book will become as indispensable for understanding contemporary China as was, and remains, McGregor’s earlier book, The Party. Indeed, much of Backlash updates The Party for the Xi era. As such, some two-thirds of the book deals with domestic politics, which will be the subject of this review.

While the “backlash” towards China under Xi is most clearly seen internationally, domestically the evidence is more tenuous and the case for a “backlash” harder to make. This is not a fault of scholarship, but rather the difficulties of writing about China’s preternaturally opaque political system under conditions of extreme censorship, even in the social media age.

McGregor’s main thesis is that Xi’s anti-corruption campaign has created powerful enemies among the families of those brought down. It could hardly be otherwise. Xi has used anti-corruption both as a legitimate means to restore the Chinese Communist Party’s standing and as a powerful political weapon against rivals.

Why then has Xi succeeded where his predecessors failed, despite also targeting corruption? The implicit answer in Backlash is that Xi is tougher and more authoritarian than his predecessors. This is probably true, but the broad popular support for the anti-corruption campaign could also usefully be acknowledged. The early gains in “capturing tigers” were popular and would have strengthened Xi’s hand to push harder.

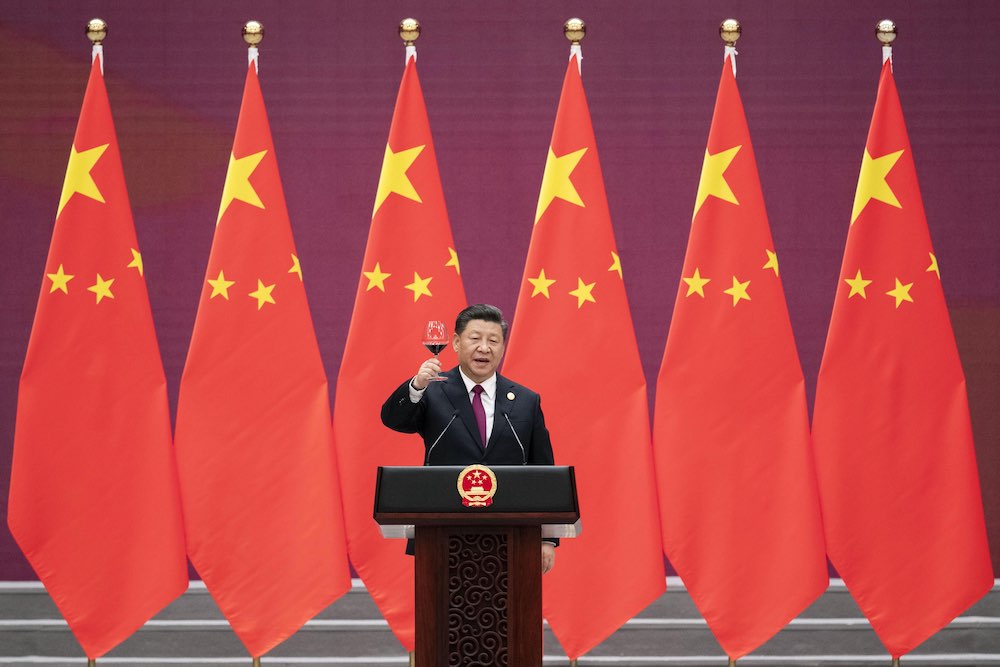

McGregor describes well the authoritarianism of Xi and the associated nascent cult of the personality. The repression of rights lawyers has been an especially dispiriting aspect of Xi’s period and one highlighted here.

Understanding why China has entered this more authoritarian period after a decade or more of gradual loosening of political control is challenging. Is it simply that Xi is a bad man, or is he himself subject to deeper structural forces?

Xi’s era coincides with the end of one of the most important aspects of Deng Xiaoping’s reform legacy: collective leadership and the fiction of fixed terms.

By the time Xi was to assume power, collective leadership had largely broken down as the older generation had passed away and their immediate successors aged and lost influence. Consequently, Xi’s ascension could be challenged directly and was by former governor Bo Xilai, leading to the first power struggle within the elite in the reform era.

The Party had once again returned to its Leninist origins which for leaders essentially boils down to kill or be killed. The hard-won political stability of the previous decades had gone. Xi’s authoritarianism may therefore be attributed to how he secured power as much as any personality trait. And authoritarianism begets more authoritarianism.

China’s political system is now more brittle and potentially unstable than at any time in the reform period. These can better be attributed to systemic factors rather than the will of one man.

China’s political system is now more brittle and potentially unstable than at any time in the reform period. These can better be attributed to systemic factors rather than the will of one man. Certainly, Xi has many enemies waiting to pounce when the chance arises, but these do not amount to some sort of generalised “backlash” against him.

To the extent that there is dissatisfaction with Xi among the elites – setting aside the desire for revenge from those directly and indirectly affected by his anti-corruption campaign – it is around “President for Life”. Mostly these people support one-party rule but having a “President for Life” is seen as retrograde and makes China (and them) lose face internationally.

Meanwhile, over this period, the economy has continued to prosper and has managed smoothly the transition to being consumption-led and services-based. Real per capita incomes are some 40% higher than when Xi took over.

McGregor sees economic reform in retreat, yet trends are actually in both directions. The economic reform cup has at any point always seemed to be half full, but then over time it can be seen to be filling. He also makes much of Xi’s apparent statism and preference for state-owned enterprises over the private sector. This probably has less to do with any ideological disposition than Xi’s obsessiveness about Party control and his control of the Party. In any event, over the past year or so, policy has sought to encourage small and medium-sized enterprises with preferential credit arrangements.

Similarly, while Xi has moved to insert Party representatives in private firms, it is yet to be seen what difference, if any, this will make in the actual performance of such firms and China’s entrepreneurship. China seems to have evolved a system where Party and entrepreneurs get along fine with each other.

Backlash is full of insights together with sparkling anecdotes and quotes. As a description of what is occurring, however, “backlash” does not capture the nuances of the complex interplay of forces in this transformative period in China. Much more is at work than just one man. Xi has sworn enemies and many hold grievances, but many more support him and the system of which he is a creature.

As McGregor speculates in the introduction, with the instruments of control in the surveillance state that China is fast becoming, the West may find it has an enduring competitive model. The risk to this happening comes entirely from the smallest circle within the elite. For the time being, they have decided to hang together rather than hang separately.