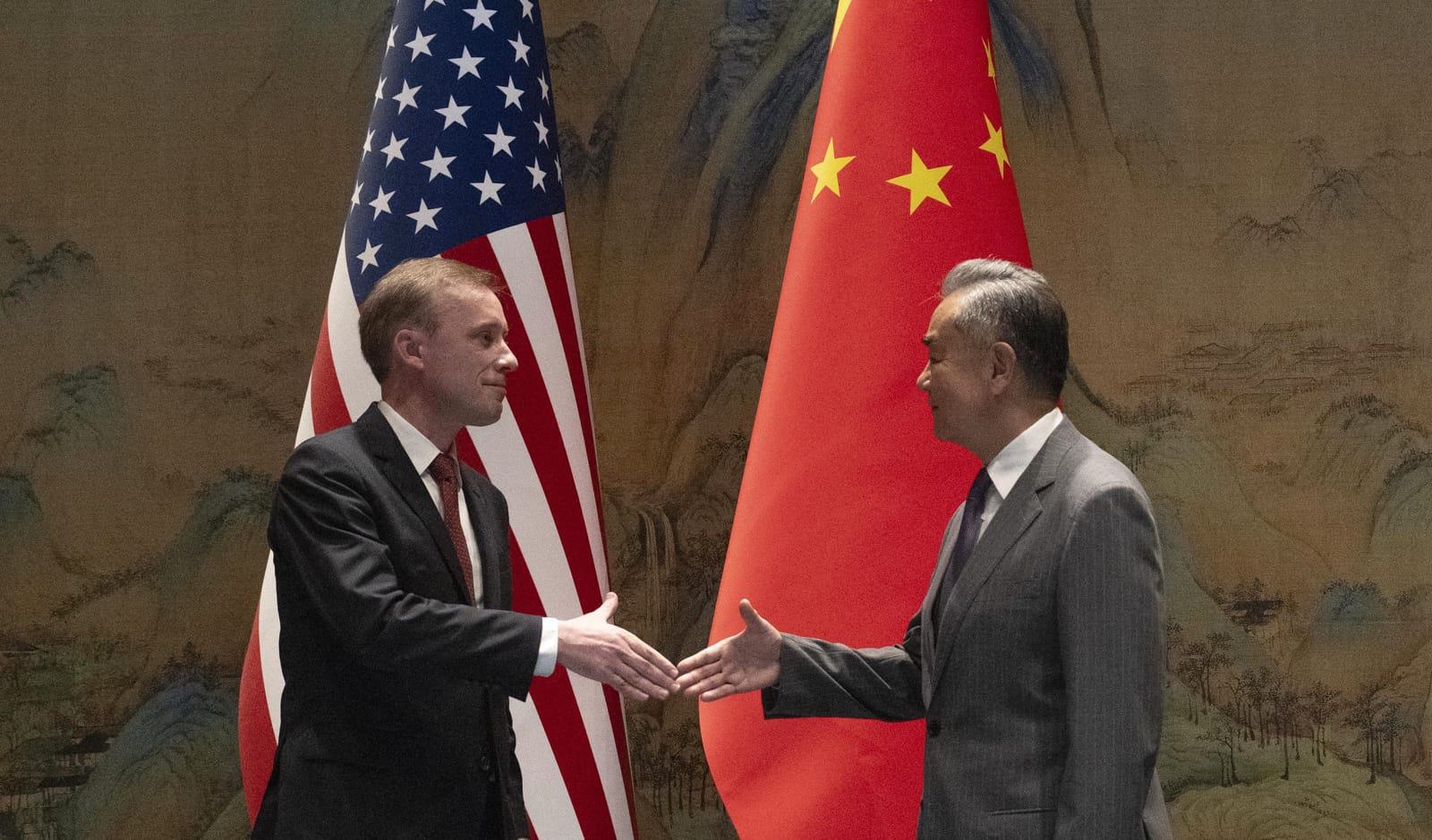

Last week, US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan travelled to China for a multi-day trip in an attempt to keep relations between Washington and Beijing on a somewhat even-keel as the United States prepares for a political transition in several months’ time.

The trip was notable in several respects. It was the first time in eight years that a US national security adviser made the trip to Beijing, and Sullivan managed to grab a meeting with General Zhang Youxia, the Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission. The mere fact that this specific meeting occurred, after a two-year freeze in communications with its military officials, suggests that China’s President Xi Jinping is as interested in maintaining stability over the proceeding months as the Biden administration is.

The readouts of the conversations don’t tell us much. On the US side, the word of the day was “responsibility,” as in both superpowers have a responsibility to ensure the competition between them doesn’t veer into a conflict. While this phrase has taken on a robotic-like character over the years, it happens to be true.

The consequences of a direct US-China conflict, either over Taiwan, the disputed shoals of the South China Sea or by sheer miscalculation, are unfathomable. One war-game conducted earlier in the year assessed that tens of thousands of US service members would be lost in addition to dozens of ships and hundreds of aircraft. The economic repercussions would be just as gargantuan, with perhaps as much as 10 per cent of global gross domestic product wiped out.

Systemic rivalry aside, the US and China don’t have an interest in flirting with such a catastrophic scenario. To the extent Sullivan’s meetings reinforced this theme, then they were time well spent.

But nor is there much room for problem-solving among US and Chinese officials at this particular time. Indeed, just as Sullivan stressed the urgency of responsibly managing relations, he also made it clear that Washington wasn’t going to reorient its China policy. American technologies that could contribute to the modernisation of China’s People's Liberation Army (PLA) will continue to be restricted. Sullivan called out China for its repeated use of so-called “grey zone” tactics around the Sabina and Second Thomas Shoals, designed to interrupt Philippine re-supply missions. Taiwan will remain the biggest point of contention, with Sullivan yet again denouncing any moves by China to settle the issue by force.

China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi was equal parts scathing and diplomatic during his time with Sullivan, arguing that the United States needed to start treating China as an equal rather than a systemic competitor. In fact, Chinese officials completely disagree with the notion that the United States and China can be a competitor and a partner at the same time. On the South China Sea, Beijing wants the United States to stay out entirely. Xi remains emphatic that US export controls are as much about preventing Chinese economic development as they are about constraining the PLA. Short of outright US capitulation to Chinese demands, there is little Washington can do to assuage Beijing on any of these matters.

These nuts-and-bolts interactions won’t get diplomats and leaders into the history books, it’s the best Washington and Beijing can do at this specific time.

Sullivan’s trip notwithstanding, US-China relations at an institutional level won’t improve dramatically. The reasons for this have less to do with individual personalities – US foreign policy analysts have a habit of obsessing about Xi’s personal qualities – and more to do with high politics. Structurally speaking, the United States and China may be bound for an inherently confrontational relationship for the next several decades by virtue of their respective positions in the world.

The United States seeks to maintain its dominance over international relations to the extent possible, whereas China (as all aspiring superpowers do) is intent on translating its greater wealth and military capacity into more power in the international system. The latter will obviously rub up against the former, resulting in the type of bilateral tension that is not easy to rectify. Throw in completely different governing ideologies as well as a tendency by US politicians to browbeat China for domestic political reasons, and the long-term trajectory of relations looks ominous to even the most optimistic observer.

The United States and China, therefore, are probably relegated to tackling disagreements on the margins with the aim of controlling the mutual tension that exists. Although these nuts-and-bolts interactions won’t get diplomats and leaders into the history books, it’s the best Washington and Beijing can do at this specific time.

A key component of this tension-reduction strategy is face-to-face dialogue that is long-lasting, durable, and persists for the long term regardless of who happens to be sitting in the Oval Office. To its credit, the Biden administration understood this from the beginning, even if its actions – the hysterical reaction to “Balloongate” in early 2023 being the most infamous – can complicate the very dialogue it hopes to preserve.

Sullivan’s discussion with Wang last week was just the latest in a series of exchanges dating back to May 2023, when the two agreed to establish a diplomatic channel among themselves to address crises as they arise.

China hawks in Washington will continue to dismiss meetings such as these as pointless at best, and borderline appeasement at worst. What, they may ask, is the point of entertaining meetings when the sole deliverable is more meetings? But there’s another question that all too often gets sidestepped: is a form of diplomatic isolation a viable alternative?