The digital age has changed the work of foreign correspondents for ever, delivering breaking news and raw video from far flung places at unprecedented speed.

It’s allowed faster filing from more locations than ever before.

But the fundamentals of good journalism remain and the value of reporting from foreign correspondents has only increased.

As government forces lay siege to the opposition held east of Aleppo last year, and Russian airstrikes rained down, we were still able to conduct interviews, and in some cases see footage of the bombs falling just an hour or two after they exploded, thanks to the wonders of social media and digital communications. They are incredibly powerful tools.

I conducted an interview by Skype as a makeshift ambulance raced off to the latest airstrike. And I received voiced messages from activists, documenting the dying days of opposition control over a city that had become an icon of the uprising against Bashar al Assad, then the descent into civil war and jihad.

And yet for all of that so called 'connectivity', the pitfalls are many. Fake posts and imprecise sources abound. Distressing images fuel waves of Twitter outrage that soon break on the shores of Realpolitik and a hard power that remains immune to the sentiment of audiences far from the fray.

And, while you might think this odd coming from someone who has spent most of his professional life documenting these outrages, I have an ill-defined feeling that the more remote we are, the more exploitative our use of those images can become.

The immediacy and frequency of images, flooding in via WhatsApp, Twitter and Facebook, can also rob us of one of the few benefits of being at a distance: the chance to seek a broader view.

While the tools of journalism are changing, the rules have not. Scepticism and cross referencing remain essential. You’ve got to be a bit old school to make the new school worthwhile.

I tend to only use digital sources I’ve already met in person. I’ll go one level out from them if the accounts of those people are consistent with the broader context, other sources or have been proved correct in previous conversations.

And the fact is, despite the joys of connectivity, nothing substitutes for simply being there; for having the time and money to go into the field, hike across the border, or visit the aid workers and displaced locals nearby, to speak face-to-face with people at the centre of the story.

The body of work that won this year’s Lowy Institute Media Award was generated over seven months, covering the battle against the Islamic State group in Mosul. Some of it was produced from a distance but it was all based on repeated reporting trips to the front lines and refugee camps of northern Iraq.

Only by returning to the field were we able to follow up with a Kurdish fighter who had, as he’d hoped, been reunited with his mother after she’d lived for two years under IS rule. And only once we were sitting with him in that village did we discover, in a bitter irony, that his sister’s house and her entire family had also been wiped out in an airstrike as his forces, backed by the US-led Coalition advanced on the area.

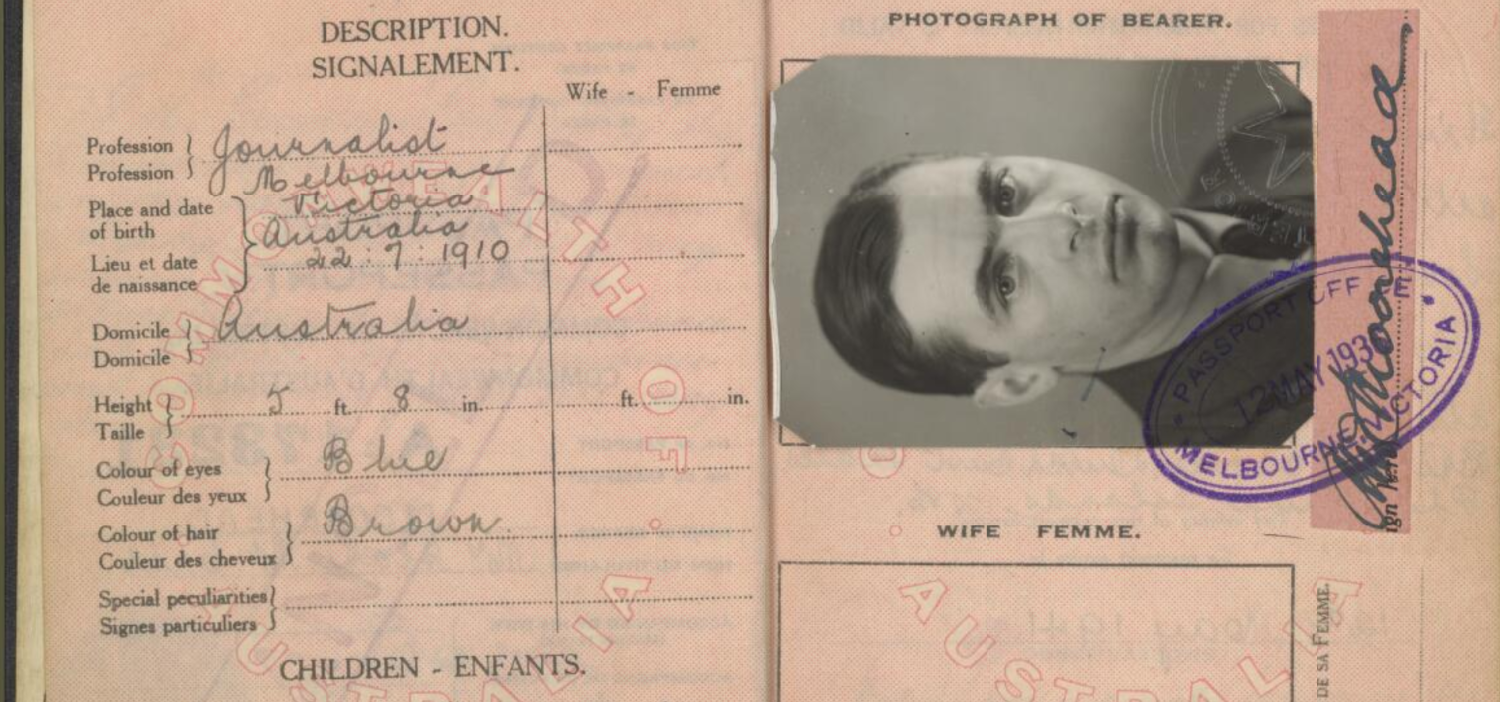

[[{"fid":"187686","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default","alignment":"","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"3":{"format":"default","alignment":"","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false}},"link_text":null,"attributes":{"height":376,"width":800,"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"3"}}]]

On the march with Iraqi troops in Mosul

When I’m not in the field, as a sort of antidote to the flood of information, I’ve also found myself referring increasingly to the products of the first information revolution: books. Reference books, atlases and accounts by academics, human rights workers, diplomats and soldiers provide critical context and history.

In another mix of old and new, when there’s a lull, I use an internet connection to the Australian National University’s library, to access peer reviewed journal articles, dipping into the sharpest accounts of work by some of the world’s greatest researchers.

To be truthful there isn’t often a lull and at home, the digital age has allowed a far greater intrusion on family life as 4G technology, internet video, and increasingly rapid file transfers allow gathering and filing at all hours.

The filing cycle often demands work in the evenings to cater to the morning bulletins in Australia, If there’s a big story, I’ll grab a quick bite of dinner, then cross live into News Breakfast somewhere between 9pm and 11pm my time, depending on the seasons.

But for all the digital transformation, for me, it would be impossible to manage without a crucial, non-digital resource: the support of a generous partner. My wife, Toni O’Loughlin, gave up her job as a journalist in the press gallery at parliament house in Canberra to come with me to Jerusalem in 2005. And since then she’s acted as chief financial, logistical and editorial counsel.

Like the partners of many a foreign correspondent she has frequently had to raise our child single handed. When Syria was blowing up and Egypt was melting down in 2013, I think I spent more than five months out of the country. More often than not she is the one here in Beirut doing the shopping, and ordering the gas bottles for cooking, and the diesel fuel deliveries for hot water.

It’s no exaggeration to say that the torn shoulder ligament she now suffers is due in large part to carrying that load.

But she hasn’t backed off. She is completing a Master’s degree in Arabic and Islamic Studies and frequently comes up with story ideas and crucial analysis. In fact, if you’re wondering about the role of unions in unrest on the Arabian Peninsula in the 1950s, or holes in Saudi Arabia’s plans to reform its oil economy, then you can just drop in to our place for coffee between breakfast and school drop-off time when the conversation delivers far more insights than Twitter and Facebook combined.

The digital revolution has certainly transformed the work of a foreign correspondent but the information, no matter how abundant, is only as good as the people behind it. And that’s a rule that’s held true through every age.

All photos by the author