This is the first in a three-part series of articles examining the Democrats’ and America’s place in the world in the lead-up to the US presidential election. The second article can be read here and the third here.

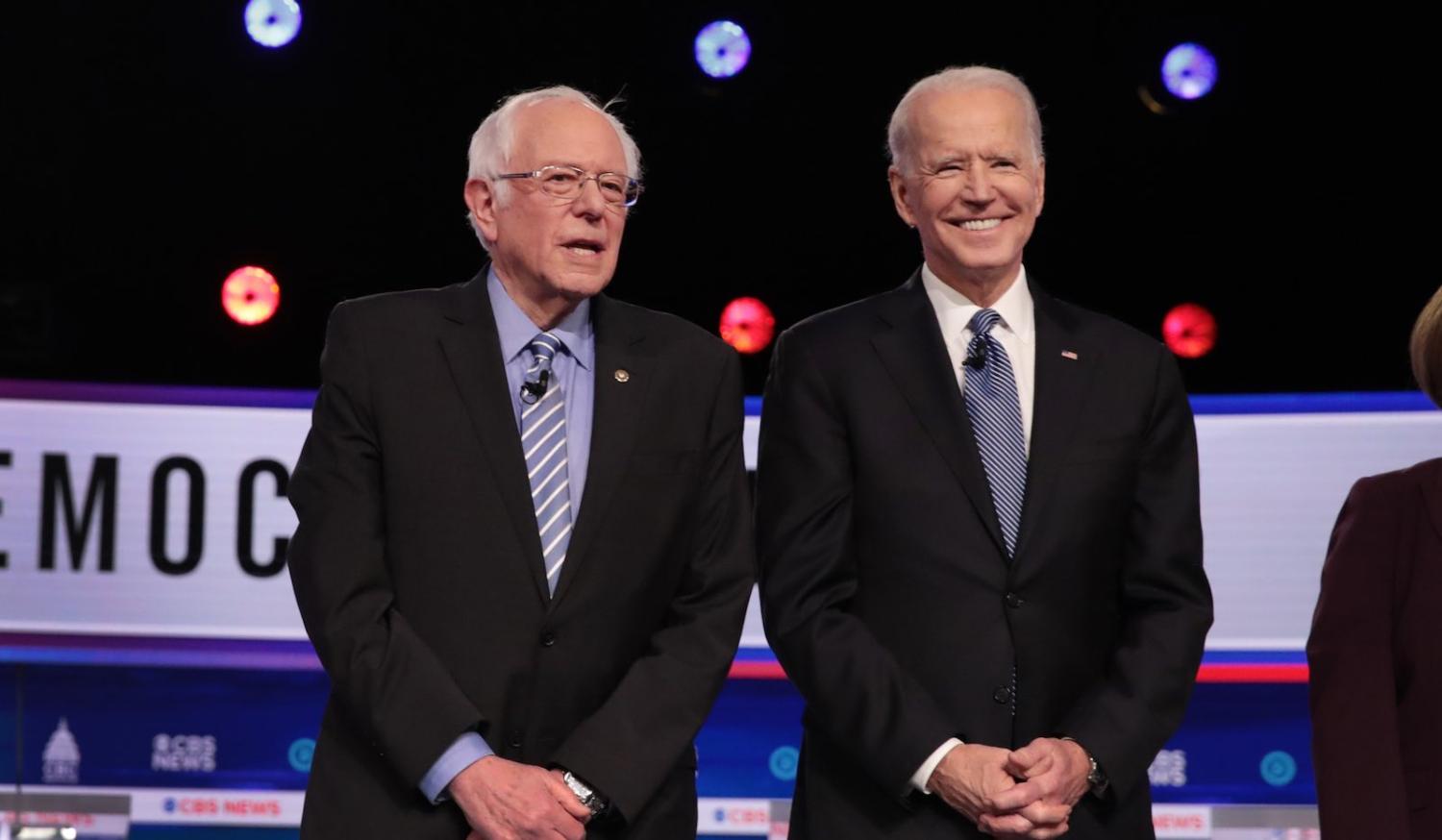

The Democratic presidential contest unfolding in America presents the party of modern American liberalism with a stark choice between two utterly different candidates.

This is a choice between the high-taxing, radically progressive climate change, health, and education policies of Senator Bernie Sanders and the centrist approaches of former Vice President Joe Biden. The choice is at once about who has the best chance of beating President Donald Trump in November’s election and about the future shape of America.

It would be a mistake to view the contest as simply one over domestic economic and social policies, even though these dominate the campaign. America’s place in the world is also up for grabs. The voters have yet to have their say, but there is potentially much at stake for Australia and the Indo-Pacific.

The campaign focus on domestic issues tends to mute somewhat the differences between Democratic progressives and centrists on foreign policy. But these exist and are important. Biden is a known quantity on foreign policy. Sanders decidedly is not.

The centrist and progressive camps of the Democratic Party critique US foreign policy under Trump in broadly similar terms. They argue he has alienated allies, emboldened autocrats, left American diplomacy in tatters, and “trashed” the sources of US soft power abroad, particularly its ability to lead on the basis of “American values”.

Withdrawal from the Paris climate change agreement and the nuclear deal with Iran has damaged US credibility and weakened US global leadership. Trump has confronted China without effectively competing with it, and his “clumsy” trade war has hurt American farmers and manufacturers.

Joe Biden argues things have gotten so bad US foreign policy needs “rescuing” more than it does rethinking.

So much, then, for what the Democratic Party candidates stand against. What do they stand for?

Biden says he will take “decisive steps” to renew America’s “core values” so that the US can lead by the power of example. Sanders also calls for a foreign policy that “clarifies our commitment to democratic values both at home and abroad”. Liberty, accountability, and the rule of law are the starting points. These foundation stones of American democracy are to be restored at home and asserted abroad, including by standing up to authoritarian regimes like China and Russia.

Both Biden and Sanders endorse a green “new deal” – a “national mobilisation” against climate change that covers emissions, investment in technology, infrastructure, and economic and social adjustment packages. The candidates have pledged to rejoin the Paris agreement. Biden has committed to a net zero emissions by 2050 target, and Sanders argues for “complete decarbonisation” by that date.

There are some important differences in the detail of these climate change policies, including on nuclear power, gas, and the respective roles of government and the private sector, as this useful summary shows. Even so, the shared ambition on climate change across the progressive-centrist divide is palpable. Australia will be on notice if the Democrats win the presidential election.

Elsewhere, there are promises to restore America’s regard for allies and close partners. Both progressive and centrists want to get the US out of the “forever wars” in Afghanistan and the Middle East, albeit with some variations on how a drawdown should be achieved and what should be left behind to focus on counterterrorism. Moreover, America should learn from the strategic and moral disaster of the Iraq intervention: military force should be the last option, reserved for direct threats to America or to avert mass atrocities, for example. Diplomacy is to be privileged.

Another striking feature of the Democratic primaries is the strong emphasis on working families and the US middle class. This reflects now-mainstream concerns about the negative effects of globalisation, particularly the swathe cut through US manufacturing in recent decades by trade competition and automation. Nor can any Democratic Party candidate afford to cede this political ground to Trump’s brilliant ability to tap into American discontent.

Sanders sees globalisation as the enemy and free trade agreements as a problem, not an opportunity – just one part of an overall economic model that has to be radically overturned to reduce inequality and drive, as he sees it, fairer and more sustainable economic growth. But even Biden and his fellow centrists won’t contemplate new trade deals without significant conditionality.

Some Democratic Party foreign policy thinkers go further. Jennifer Harris and Jake Sullivan, for example, argue that America’s foreign policy establishment needs to contribute a geopolitical perspective to the debate on what should follow economic “neoliberalism”.

This is not just about rethinking the net effects of free trade, but looking afresh at other economic policy approaches once banished under the Washington Consensus, like industry policy for example. Harris and Sullivan argue US firms will continue to lose ground to China if Washington relies solely on private-sector research and development. Some on the Republican side of US politics make the same arguments, a remarkable shift away from the primacy of free markets and private enterprise.

Not much has been said yet on responding to the Covid-19 pandemic, with its hard-to-predict short- and long-term effects on the global economy and geo-politics. It seems highly likely, however, that whoever wins the presidential election will be rethinking what US resilience means in a hyper-connected world and dealing with a set of challenges and priorities not foreseen when the campaign began in earnest.

The campaign focus on domestic issues tends to mute somewhat the differences between Democratic progressives and centrists on foreign policy. But these exist and are important. Biden is a known quantity on foreign policy. Sanders decidedly is not.

Sanders wants to cut the US defence budget at a time when China’s military is closing the capability gap. He would set a much higher bar for the deployment of military force. He may trade off balancing China’s power in the Indo-Pacific for more ambition from Beijing on climate change. His opposition to free trade surpasses even that of Trump. Inevitably, a highly progressive domestic agenda would come to shape other aspects of US foreign policy. Astute observers of US politics suggest that in office Sanders could prove as revolutionary as Trump has been when it comes to America’s place in the world and how it prosecutes its interests globally.

The next article in this series will explore what these differences might mean for Australia’s interests in the Indo-Pacific.