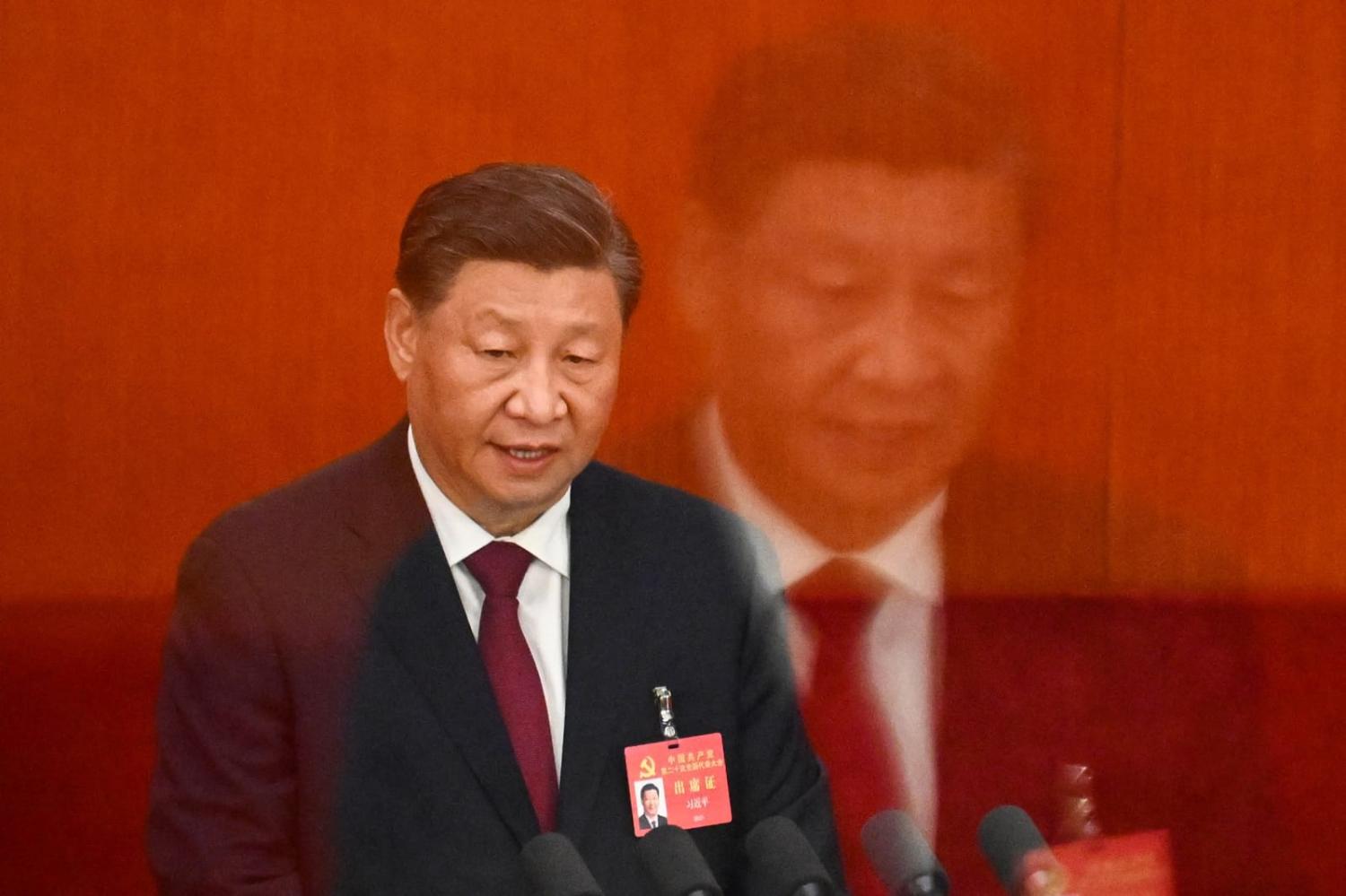

At the just completed ruling Communist Party Congress, Xi Jinping was re-selected as head of the Party. Many analysts argue that Xi’s personal power consolidation has eliminated restraints within the Party by removing term limits and exploiting an anti-corruption campaign to get rid of rivals. In doing so, Xi has established a network of loyal protégés and made himself the most powerful ruler since Mao Zedong. However, the assumption of Xi’s sweeping power might be overstated. Instead, his personal political dominance could be constrained by internal factors, including his trusted allies.

Both Xi and his allies have common interests in securing regime survival, including retaining his dictatorship to prevail over political rivals and to further policy objectives.

However, these same allies will also inevitably compete with each other to enhance their personal power, building their own patron-client networks, influencing policy and even military affairs in order to secure their standing against lower-level supporters. This power struggle is likely seen as coming at the expense of others within the ruling coalition. Consequently, as Xi seeks to accumulate more power, he must be wary of the threat of a divided coalition led by discontent associates.

There was evidence at the time of Mao’s rule that his allies sought to obstruct their leader’s personal power. As a recent book, Coalitions of the Weak, by University of California researcher Victor C. Shih details, in the 1950s Mao put his protégés into the Party’s highest positions to reward them for support in the First Front Army. By later that decade, however, as Mao confronted the damage to his reputation from the collapse of the Great Leap Forward campaign, a rival coalition that included his loyal allies Zhang Guotao and Lin Biao attempted to act independently. Zhang led the foundation of a Provisional Central Committee composed of his followers to call for the expulsion of Mao from the CCP. Likewise, Lin Biao – a prominent military commander and one of Mao’s closest allies – later sought to consolidate his individual power by controlling the Central Military Commission Administrative Office consisting of his advocates against Mao’s Central Military Commission Standing Committee.

There is no debating that Xi and his protégés have sought to dominate via personal power. But there are also signs that could be interpreted as resultant rivalries. Wang Qishan – one of Xi’s key allies – was known as an instrument in the concentration of Xi’s rule since 2013, having served as a “key player” in Xi’s anti-corruption drive and confronting domestic financial problems. However, Wang had also built his own network in both the financial sector and anti-corruption bureaucracy. He has now been excluded from the Politburo Standing Committee and appointed to a symbolic vice-presidential position, albeit while smiling and shaking hands with Xi.

Serving as one of Xi’s allies could be a tightrope walk if he becomes suspicious of their loyalty. For instance, Fu Zhenghua – a former Beijing police chief – had supported Xi by suppressing online dissent. Fu had won Xi’s trust, resulting in his appointment as a leader of the Zhou Yongkang corruption case. However, Fu then fell himself to accusations of graft and disloyalty to the Party and was imprisoned in 2021.

Xi’s willingness to remove protégés that he sees as disloyal implies that those who are in his ruling coalition today might not be tomorrow. As authors Barbara Geddes, Joseph Wright and Erica Frantz have described in relation to the functioning of dictatorships, trust is rare and Xi constantly needs to invest political resources to protect his own position. Xi’s protégés have every reason to seek to limit Xi’s individual power, particularly his control of the military and police, which Xi could turn against them. As Professor Yuhua Wang of Harvard University has noted, “it’s not that people are following him voluntarily, it’s actually that people are following him because people worry about the risks of not following him”. Wang goes on to explain that while Xi appears to have no political opponents, “at least publicly”, and be surrounded by officials that appear loyal and compliant, “they might be hiding their true feelings … [and] when everybody becomes quiet and then they comply, I think it’s very dangerous for the top leader”.

On the surface, and embarking on a third term, Xi could be seen to have replaced the collective leadership model in China. But as he strives to consolidate personal power, Xi may also have to face up to the restraints borne of competition among his loyalists.