On 21 May, voters in Timor-Leste will head to the polls for the country’s fifth parliamentary election since 2002. Elections in one of Southeast Asia’s most vibrant democracies are always a competitive affair, and the Timorese treasure their right to vote because the simple act of casting ballots secured their path to independence in 1999.

The five years since the 2018 election have been marked by political tumult – cohabitation, gridlock, a change in government, and a change in president – that has led to inconsistent policymaking and hindered the maturation of institutions. As polling day approaches, two factors will shape the electoral environment – one rooted in the past and one crucial to the country’s future.

Xanana Gusmão versus Mari Alkatiri

The relationship between Gusmão and Alkatiri, who lead the country’s two largest political parties, is one of the defining features of Timorese politics. As I wrote last year:

Relations between Gusmão and Alkatiri have long been contentious – some of their mutual animosity stems from the fact that the former was in the country during the occupation, while the latter was in exile outside of the country. Each has distinctly different personal styles. Gusmão is known for his charisma, while Alkatiri is a relatively quiet operator…

In recent years, the two have been engaged in a shadowboxing match of sorts, each trying to knock the other out of politics. Every time one of them gets knocked down – whether by the defeat of the Alkatiri-led minority government in 2018 or deposition of the Gusmão-backed government in 2020 – they get back up and throw a return punch.

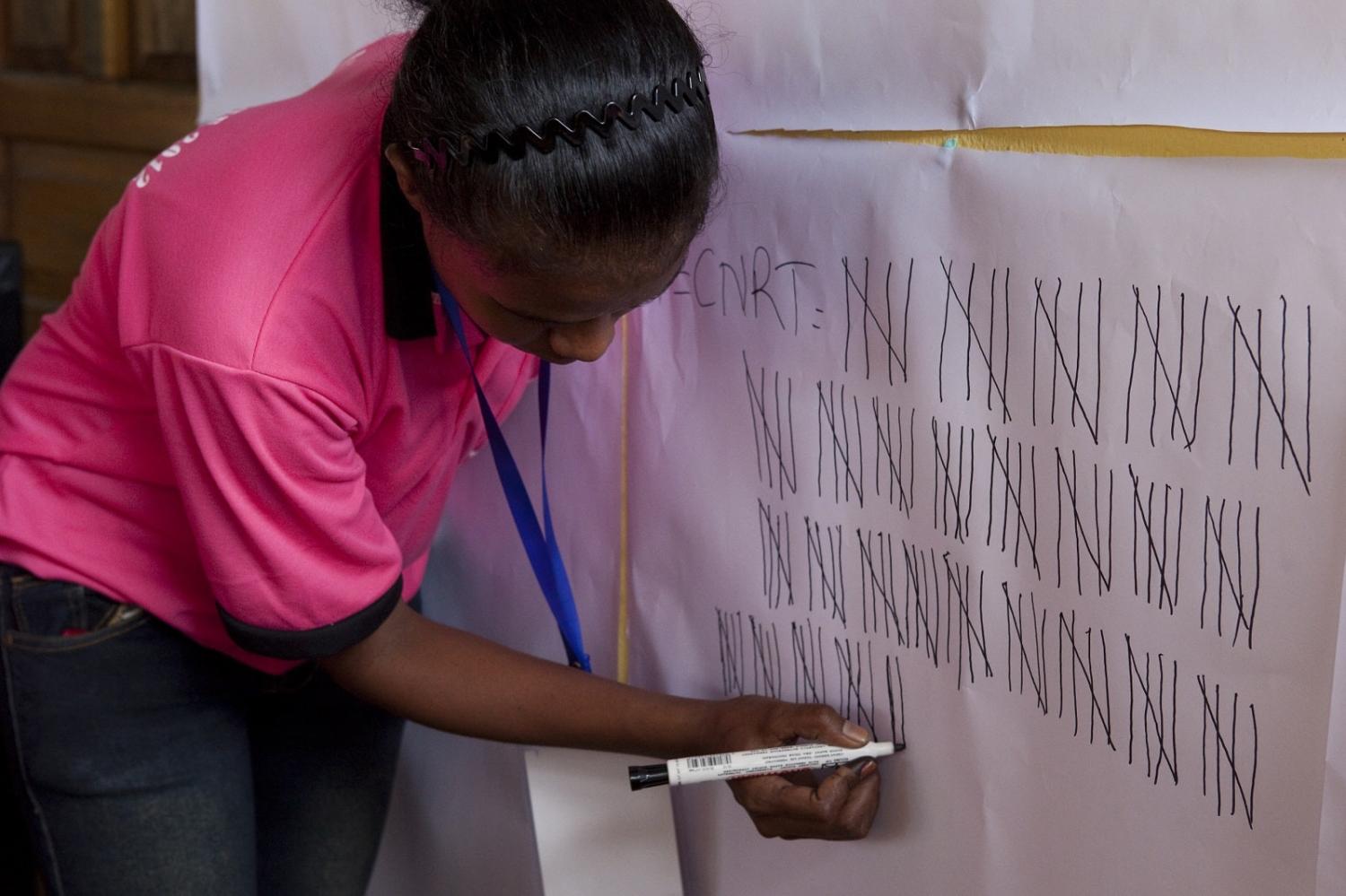

May’s election will be yet another round in their feud, with Gusmão’s National Congress for Timorese Reconstruction (CNRT) seeking to push Alkatiri’s Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (FRETILIN) out of government. While there is currently no public polling available, anecdotal evidence and the 2022 presidential election results point towards CNRT being the early favourite.

Neither party seems poised to form a pre-election coalition, as CNRT did with the Majority Alliance for Progress (AMP) in 2018, so it will come down to who wins a plurality of the vote. Under Timor-Leste’s constitution, the party who does so gets the first chance at forming a government, as FRETILIN did in 2017 when they unexpectedly bested CNRT by 1,135 votes.

Greater Sunrise

Developing the Greater Sunrise hydrocarbon field, which lies off Timor-Leste’s south coast, is imperative to the country’s economic future. Doing so has been delayed by long-standing disagreement between the field’s joint venture partners – Timor Gap, Woodside Petroleum and Osaka Gas – over whether to process liquefied natural gas (LNG) from it through existing infrastructure in Darwin, Australia or new infrastructure in Timor-Leste, under the colloquial banner of Tasi Mane.

Needless to say, the issue carries significant political implications. As I wrote last March in the context of the presidential election:

In securing Gusmão’s endorsement, President José Ramos-Horta also indicated support for Tasi Mane … There are numerous questions about the project’s cost and viability – part of why the current FRETILIN government essentially paused it – but it is Gusmão’s top priority, and he sees it as his legacy.

If the project is resumed, the country is “betting the house” on it working and delivering the promised economic benefits. If it doesn’t, the country may miss out on much-needed oil and gas revenue and face an economic cliff in the late 2020s or early 2030s. The cost of the project necessitates international investment, which opens the door to investment-driven geopolitical competition.

Gusmão has long been the leading advocate for Tasi Mane and sees it as his legacy. While in government, Alkatiri’s FRETILIN has been lukewarm towards the megaproject, essentially pausing it in 2020. Ramos-Horta, who is aligned with CNRT and was endorsed by Gusmão during his presidential campaign, has vocally promoted the project on the international stage in a thus far unsuccessful effort to resolve the deadlock between the joint venture partners.

Economic issues will feature as both parties barnstorm the country, seeking to persuade voters that their position on Tasi Mane and Greater Sunrise is the correct one. Don’t expect the policy details to receive much attention, though; instead, they will wrap it in the flag, as Timorese campaigns are driven by resistance-era credentials and national identity more so than party platforms and policy priorities.

The prospect of a united government between Ramos-Horta and a CNRT-led parliament and executive is enticing for Gusmão, and he is already arguing that electing his party will restore stability – something that voters may desire – and deliver the promised economic benefits of Tasi Mane. FRETILIN will aggressively contend those assertions, and it maintains a rock-solid support base that makes it competitive at every election.

Several political parties will be on the ballot, but the contest between CNRT and FRETILIN – and Gusmão and Alkatiri – will define the election. It will be closely watched by the international community because of the ramifications it holds for two high-profile transnational issues – geostrategic competition and democracy – that exceed the island nation’s size.