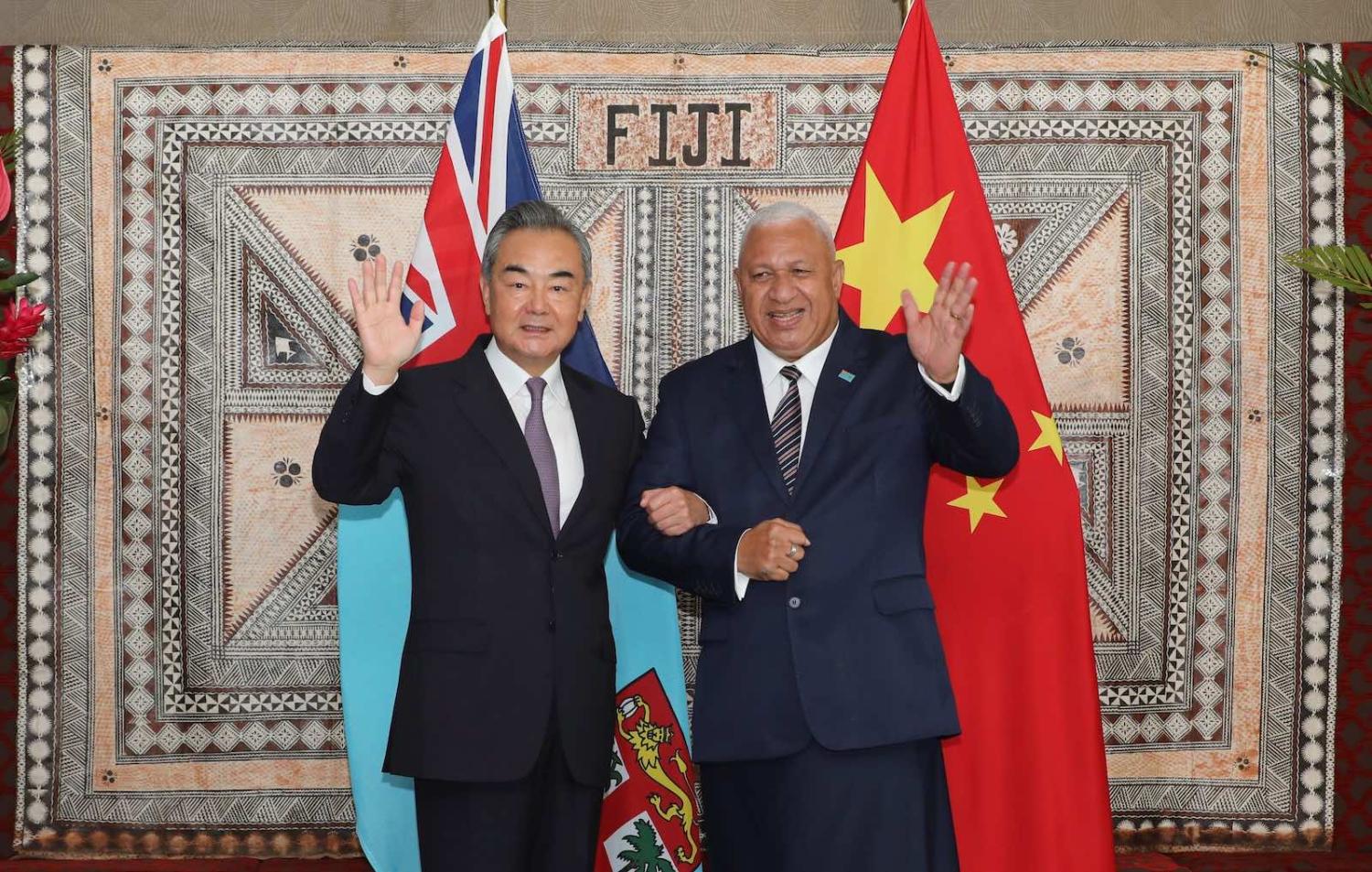

Earlier this month, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi concluded a 10-day tour of the Pacific, touching down in Solomon Islands, Kiribati, Samoa, Fiji, Tonga, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, as well as Timor-Leste (skipping Nauru, Palau, Tuvalu, and the Marshall Islands, which maintain relations with Taiwan). On 30 May, Wang hosted a virtual conference that included the Federated States of Micronesia and Niue, unveiling a sweeping proposed regional pact titled “China-Pacific Island Countries Common Development Vision” encompassing trade and investment, public health, police training and cooperation, cyber security, maritime mapping, surveillance, and disaster recovery.

Yet Wang Yi’s trip did not go as smoothly as planned. After China’s ground-breaking security deal with Solomon Islands in April, it hoped to secure a similar agreement with 10 Pacific Island nations. While an impressive 52 bilateral cooperation deals were signed, the regional pact was not. This raises questions about the extent to which, and why, China stumbled.

One answer is that what has worked well for China in Africa didn’t translate neatly to the Pacific. Broadly put, China’s approach in Africa has focused on trade and investment as vehicles to build influence. Economic engagements are facilitated by relationship-building among state elites, development assistance targeting health, training, and agriculture, and high-profile infrastructure projects constructed by Chinese multilateral companies financed by Chinese state-owned banks. When China started encouraging its companies to “go out” and increase investments abroad in the late 1990s, they went to Africa in droves, with China surpassing the United States to become Africa’s largest trading partner in 2009.

The Pacific Islands have witnessed a similar trajectory, with China building its presence over the past two decades through trade deals, infrastructure projects, development assistance, high-level diplomacy, and, more recently, integrating the countries into the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Chinese companies constructed a sports stadium to host the Pacific Games in Solomon Islands, highways in Papua New Guinea, and bridges in Fiji. It has sent several high-level envoys to the region, including Premier Wen Jiabao in 2006, President Xi Jinping in 2014 and 2018, and now the foreign minister.

Perhaps China’s intention to shift its relationship with Pacific Island nations towards a multilateral structure backfired because China underestimated both their strengths as individual nations and their collective will as members of the Pacific Islands Forum.

In the process, China has become a major trading partner for Pacific Island economies. Since 2000, there has been a twelve-fold increase in the value of Chinese exports to the region. Evidence from Africa also suggests that China will try to parlay stronger economic relations into a military foothold in the Pacific, to support military ambitions within the “nine dash line” in the South China Sea and in relation to Taiwan. Following accelerating economic ties and financing for major infrastructure projects beginning in 2000, China built its first overseas military base in Djibouti in 2016, signalling a shift towards a more expansive and security-driven Chinese foreign policy that is now in evidence in the Pacific.

Yet the somewhat tepid local reactions to Wang’s trip also reinforce that the Pacific Islands are not Africa. Different historical relations may be a factor. In Africa, China emphasises its 1960s era support for liberation movements against European colonialists and positions itself as fundamentally different from Western powers through a rhetoric of mutually beneficial “win-win” relations between developing countries. In the Pacific, China may find it harder to present itself as the benign power due to its apparent regional ambitions and because the other dominant partners Australia, New Zealand, and the United States have long-established, friendly regional relations.

Moreover, in Africa, China successfully shaped a new multilateral structure in the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), which provides a framework for China-Africa relations within which bilateral deals are made, in part because the African Union and regional blocs struggle to leverage their collective clout vis-à-vis China. Perhaps China’s intention to shift its relationship with Pacific Island nations towards a multilateral structure backfired because China underestimated both their strengths as individual nations and their collective will as members of the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF). While China is trying to work outside of the PIF, as this includes Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific Island countries that recognise Taiwan, it may find that it must engage with it.

As noted elsewhere, a key parallel between China’s approach in the Pacific and Africa is that the exponential growth of Sino-African relations was a response to lacklustre relationships with other partners. As Chinese influence in the Pacific increases, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States should focus on strengthening their own climate change policies to reassure Pacific Island nations that they truly understand the existential threat posed by rising sea waters, while increasing trade and investment. Australia highlights that it is the regions’ biggest donor while Chinese aid is declining, but that misses the point that Chinese influence isn’t about development aid (and that in 2016, China overtook Australia as a trade partner to the Pacific Islands).

Wang’s trip highlighted that Pacific Island nations seem keen on shaping their relationships with competing partners on their own terms. As they navigate the increasing attention afforded to them by China, they should heed lessons from what has worked well for Africa – and what has not.