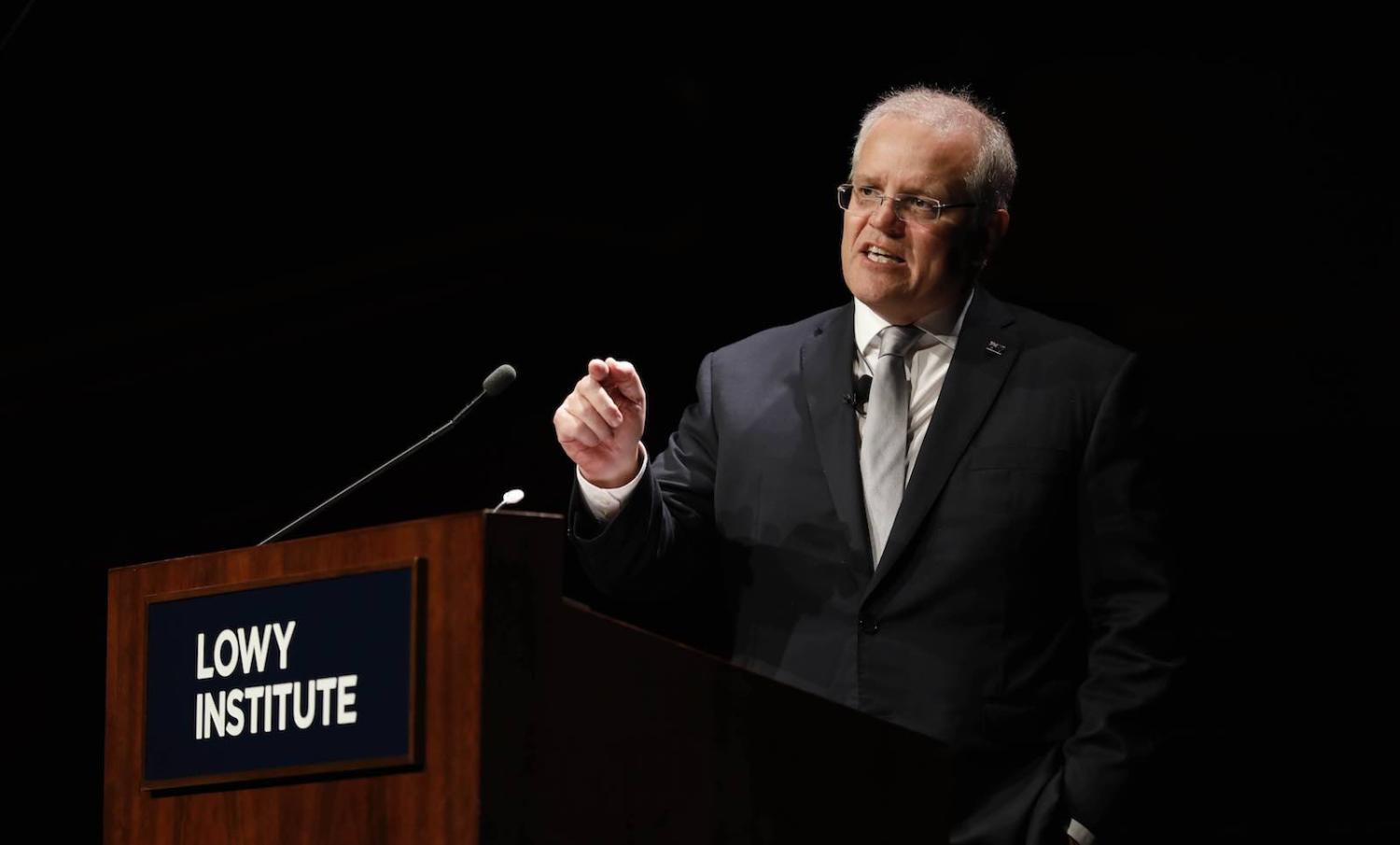

After a couple of thoughtful speeches to Asialink and the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s Lowy Lecture last night marked a clear step away from the sort of Australian foreign policy articulated in the government’s 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper and towards the worldview of Trumpism and Brexit. It looked like the trailing away of a decades-long period of Australian commitment to an open globalising world and a rules-based international order (a phrase not mentioned in the PM’s speech).

As a speech – that is, the persuasive articulation of an argument – it lacked structure or, indeed, much of an argument. It had some of the familiar elements of what was shaping up as a Morrison doctrine – the connection between what happens externally and the practical needs of ordinary Australians. But the tone this time was much more defensive.

I can’t remember a foreign policy speech by an Australian Prime Minister in which the words “sovereign” or “sovereignty” appear so often.

One thing is certain. No future Australian Prime Minister will be able to outdo Scott Morrison in rhetorical support for the American alliance.

Morrison warned about a “negative globalism that coercively seeks to impose a mandate from an often ill-defined borderless global community. And worse still, an unaccountable internationalist bureaucracy”. This “new variant of globalism”, the PM told us, “seeks to elevate global institutions above the authority of nation states to direct national policies”. This is a strange claim in a period in which multilateral institutions are weaker in almost all regards than they have been for 40 years.

We were offered no examples of how this might be happening to us. We were simply told that it “does not serve our national interests when international institutions demand conformity rather than independent cooperation on global issues”. How “conformity” differs from adherence to agreed rules is left unclear.

As though there were any doubt, the Prime Minister felt it necessary to declare “We will decide our interests and the circumstances in which we seek to pursue them”. It’s not clear to me who we are intended to think was challenging that national right.

The anxious and inward-looking tone continues. To the familiar list of security threats from “terrorism, extremist Islam, anti-Semitism, white supremacism”, is added a new broad category which defies easy response: “evil”. Australia’s freedom, we are told, depends on our “dedication to national sovereignty, the resilience of our institutions, and our protections from foreign interference”.

In any speech of this sort, the listicles – which countries get named and in what order – matter. What is striking here are the adjectives describing Australia’s relations with India, “a natural partner for Australia”, Japan, “steadfast friendship and support”, Vietnam, Indonesia, and ASEAN. China, on the other hand, is left with the official designation “comprehensive strategic partner” and a list of economic achievements which add up to reasons it should take on greater global economic obligations. It’s a balder, less optimistic tone than that of Morrison’s own Asialink speech a few weeks ago.

The word “practical”, a familiar friend in Coalition discourse, gets a good workout. Echoing John Howard’s “practical and realistic” foreign policy and “practical reconciliation”, the Prime Minister delivered us “practical conservation”. He contrasts the “anxiety-inducing moral panic and sense of crisis evident in some circles today” (presumably about climate change, although the phrase is not used) with the “practical resilience, optimism, and resolve” which marked earlier periods of global challenges such as the Cold War nuclear competition. I can’t say I remember it that way myself.

What should Australia do about all this? Mostly, it seems, play a more active role in the setting of global standards (mainly economic). That makes good sense, but beginning the task with a request to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade to undertake a “comprehensive audit of global institutions and rule-making processes where we have the greatest stake” might hint at a different agenda.

One thing is certain. No future Australian Prime Minister will be able to outdo Scott Morrison in rhetorical support for the American alliance. “Our alliance with the United States”, he said, “is our past, our present, and our future”. Literally, our Alpha and Omega, our beginning and our end.

That sort of language makes the handling of Australia’s relations with the United States and China so odd. Australia must, the Prime Minister says, “maintain our unique relationships” with the United States and China “in good order by rejecting the binary narrative of their strategic competition”.

Hang on, I thought to myself, flicking back through the speech, didn’t I just read something about that binary narrative? Ah yes. A few pages earlier:

We have entered a new era of strategic competition – a not unnatural result of shifting power dynamics, in our modern, more multipolar world and globalised economy.

The United States government itself acknowledges that strategic competition.

When the Prime Minister concludes that “even during an era of great power competition, Australia does not have to choose between the United States and China”, after a speech that more than any other by a recent Australian Prime Minister has done just that, it seems less like wishful thinking than deliberate obfuscation.